geo.wikisort.org - Island

Surtsey ("Surtr's island" in Icelandic, Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈsʏr̥(t)sˌeiː]) is a volcanic island located in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago off the southern coast of Iceland. At 63.303°N 20.605°W Surtsey is the southernmost point of Iceland.[1] It was formed in a volcanic eruption which began 130 metres (430 feet) below sea level, and reached the surface on 14 November 1964. The eruption lasted until 5 June 1967, when the island reached its maximum size of 2.7 km2 (1.0 sq mi). Since then, wave erosion has caused the island to steadily diminish in size: as of 2012[update], its surface area was 1.3 km2 (0.50 sq mi).[2] The most recent survey (2007) shows the island's maximum elevation at 155 m (509 ft) above sea level.[3]

Surtsey, sixteen days after the onset of the eruption | |

Map of Surtsey | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Archipelago | Vestmannaeyjar |

| Area | 1.4 km2 (0.54 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 155 m (509 ft) |

| Administration | |

Iceland | |

| Additional information | |

| Official website | surtsey |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Natural: ix |

| Reference | 1267 |

| Inscription | 2008 (32nd Session) |

| Area | 3,370 ha |

| Buffer zone | 3,190 ha |

The new island was named after Surtr, a fire jötunn or giant from Norse mythology.[4] It was intensively studied by volcanologists during its eruption, and afterwards by botanists and other biologists as life forms gradually colonised the originally barren island. The undersea vents that produced Surtsey are part of the Vestmannaeyjar submarine volcanic system, part of the fissure of the sea floor called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Vestmannaeyjar also produced the famous eruption of Eldfell on the island of Heimaey in 1973. The eruption that created Surtsey also created a few other small islands along this volcanic chain, such as Jólnir and other, unnamed peaks. Most of these eroded away fairly quickly. It is estimated that Surtsey will remain above sea level until at least the year 2100.

Geology

Formation

|

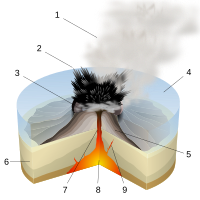

1: Water vapour cloud |

| 2: Cypressoid ash jet | |

| 3: Crater | |

| 4: Water | |

| 5: Layers of lava and ash | |

| 6: Stratum | |

| 7: Magma conduit | |

| 8: Magma chamber | |

| 9: Dike |

The eruption was unexpected, and almost certainly began some days before it became apparent at the surface. The sea floor at the eruption site is 130 metres (430 feet) below sea level, and at this depth volcanic emissions and explosions would be suppressed, quenched and dissipated by the water pressure and density. Gradually, as repeated flows built up a mound of material that approached sea level, the explosions could no longer be contained, and activity broke the surface.[5]

The first noticeable indications of volcanic activity were recorded at the seismic station in Kirkjubæjarklaustur, Iceland from 6 to 8 November 1963, which detected weak tremors emanating from an epicentre approximately west-south-west at a distance of 140 km (87 mi), the location of Surtsey. Another station in Reykjavík recorded even weaker tremors for ten hours on 12 November at an undetermined location, when seismic activity ceased until 21 November.[6] That same day, people in the coastal town of Vík 80 km (50 mi) away noticed a smell of hydrogen sulphide.[5] On 13 November, a fishing vessel in search of herring, equipped with sensitive thermometers, noted sea temperatures 3.2 km (2.0 mi) SW of the eruption center were 2.4 °C (4.3 °F) higher than surrounding waters.[7]

Eruption at the surface

At 07:15 UTC on 14 November 1963, the cook of Ísleifur II, a trawler sailing these same waters, spotted a rising column of dark smoke southwest of the boat. The captain thought it might have been a boat on fire, and ordered his crew to investigate. Instead, they encountered explosive eruptions giving off black columns of ash, indicating that a volcanic eruption had begun to breach the surface of the sea.[5] By 11:00 the same day, the eruption column had reached several kilometres in height. At first the eruptions took place at three separate vents along a northeast by southwest trending fissure, but by the afternoon the separate eruption columns had merged into one along the erupting fissure. Over the next week, explosions were continuous, and after just a few days the new island, formed mainly of scoria, measured over 500 metres (1,600 feet) in length and had reached a height of 45 metres (148 feet).[8]

As the eruptions continued, they became concentrated at one vent along the fissure and began to build the island into a more circular shape. By 24 November, the island measured about 900 by 650 metres (2,950 by 2,130 ft). The violent explosions caused by the meeting of lava and sea water meant that the island consisted of a loose pile of volcanic rock (scoria), which was eroded rapidly by North Atlantic storms during the winter. However, eruptions more than kept pace with wave erosion, and by February 1964, the island had a maximum diameter of over 1,300 metres (4,300 feet).[5]

The explosive phreatomagmatic eruptions caused by the easy access of water to the erupting vents threw rocks up to a kilometre (0.6 mi) away from the island, and sent ash clouds as high as 10 km (6.2 mi) up into the atmosphere. The loose pile of unconsolidated tephra would quickly have been washed away had the supply of fresh magma dwindled, and large clouds of dust were often seen blowing away from the island during this stage of the eruption.[5]

The new island was named after the fire jötunn Surtur from Norse mythology (Surts is the genitive case of Surtur, plus -ey, island). Three French journalists representing the magazine Paris Match notably landed there on 6 December 1963, staying for about 15 minutes before violent explosions encouraged them to leave. The journalists jokingly claimed French sovereignty over the island, but Iceland quickly asserted that the new island belonged to it.[9]

Permanent island

By early 1964, though, the continuing eruptions had built the island to such a size that sea water could no longer easily reach the vents, and the volcanic activity became much less explosive. Instead, lava fountains and flows became the main form of activity. These resulted in a hard cap of extremely erosion-resistant rock being laid down on top of much of the loose volcanic pile, which prevented the island from being washed away rapidly. Effusive eruptions continued until 1965, by which time the island had a surface area of 2.5 km2 (0.97 sq mi).[5]

On 28 December 1963, submarine activity to the northeast of Surtsey began, causing the formation of a ridge 100 m (330 ft) high on the sea floor. This seamount was named Surtla [ˈsʏr̥tla], but never reached sea level. Eruptions at Surtla ended on 6 January 1964, and it has since been eroded from its minimum depth of 23 to 47 m (75 to 154 ft) below sea level.[10]

Subsequent volcanic activity

In 1965, the activity on the main island diminished, but at the end of May that year an eruption began at a vent 0.6 km (0.37 mi) off the northern shore. By 28 May, an island had appeared, and was named Syrtlingur ([ˈsɪr̥tliŋkʏr̥] Little Surtsey). The new island was washed away during early June, but reappeared on 14 June. Eruptions at Syrtlingur were much smaller in scale than those that had built Surtsey, with the average rate of emission of volcanic materials being about a tenth of the rate at the main vent. Activity was short-lived, continuing until the beginning of October 1965, by which time the islet had an area of 0.15 km2 (0.058 sq mi). Once the eruptions had ceased, wave erosion rapidly wore the island away, and it disappeared beneath the waves on 24 October.[11]

During December 1965, more submarine activity occurred 0.9 km (0.56 mi) southwest of Surtsey, and another island was formed. It was named Jólnir, and over the following eight months it appeared and disappeared several times, as wave erosion and volcanic activity alternated in dominance. Activity at Jólnir was much weaker than the activity at the main vent, and even weaker than that seen at Syrtlingur, but the island eventually grew to a maximum size of 70 m (230 ft) in height, covering an area of 0.3 km2 (0.12 sq mi), during July and early August 1966. Like Syrtlingur, though, after activity ceased on 8 August 1966, it was rapidly eroded, and dropped below sea level during October 1966.[12]

Effusive eruptions on the main island returned on 19 August 1966, with fresh lava flows giving it further resistance to erosion. The eruption rate diminished steadily, though, and on 5 June 1967, the eruption ended. The volcano has been dormant ever since. The total volume of lava emitted during the three-and-a-half-year eruption was about one cubic kilometre (0.24 cu mi), and the island's highest point was 174 metres (571 feet) above sea level at that time.[5]

Since the end of the eruption, erosion has seen the island diminish in size. A large area on the southeast side has been eroded away completely, while a sand spit called Norðurtangi (north point) has grown on the north side of the island. It is estimated that about 0.024 km3 (0.0058 cu mi) of material has been lost due to erosion—this represents about a quarter of the original above-sea-level volume of the island.[13][14] Its maximum elevation has diminished to 155 m (509 ft).[3]

Recent development

Following the end of the eruption, scientists established a grid of benchmarks against which they measured the change in the shape of the island. In the 20 years following the end of the eruption, measurements revealed that the island was steadily subsiding and had lost about one metre in height. The rate of subsidence was initially about 20 cm (8 in) per year but slowed to 1–2 cm (0.39–0.79 in) a year by the 1990s. It had several causes: settling of the loose tephra forming the bulk of the volcano, compaction of sea floor sediments underlying the island, and downward warping of the lithosphere due to the weight of the volcano.[15]

Volcanoes in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago are typically monogenetic, and so the island is unlikely to be enlarged in the future by further eruptions. The heavy seas around the island have been eroding it ever since the island appeared, and since the end of the eruption almost half of its original area has been lost. The island currently loses about 1.0 hectare (2.5 acres) of its surface area each year.[16]

Future

As a suspected part of the Iceland plume, this island is unlikely to disappear entirely in the near future. The eroded area consisted mostly of loose tephra, easily washed away. Most of the remaining area is capped by hard lava flows, which are much more resistant to erosion. In addition, complex chemical reactions within the loose tephra within the island have gradually formed highly erosion-resistant tuff material, in a process known as palagonitization. On Surtsey, this process has happened quite rapidly, due to high temperatures not far below the surface.[17]

Estimates of how long Surtsey will survive are based on the rate of erosion seen up to the present day. Assuming that the current rate does not change, the island will be mostly at or below sea level by 2100. However, the rate of erosion is likely to slow as the tougher core of the island is exposed: an assessment assuming that the rate of erosion will slow exponentially suggests that the island will survive for many centuries.[13] An idea of what it will look like in the future is given by the other small islands in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago, which formed in the same way as Surtsey several thousand years ago, and have eroded away substantially since they were formed.[16]

Biology

Settlement of life

A classic site for the study of biocolonisation from founder populations, Surtsey was declared a nature reserve in 1965, while the eruption was still in active progress. Today only a few scientists are permitted to land on Surtsey; the only way anyone else can see it closely is from a small plane. This allows the natural ecological succession for the island to proceed without outside interference. In 2008, UNESCO declared the island a World Heritage Site, in recognition of its great scientific value.[18]

Plant life

In the spring of 1965,[19] the first vascular plant was found growing on the northern shore[20] of Surtsey, mosses became visible in 1967, and lichens were first found on the Surtsey lava in 1970.[21] Plant colonisation on Surtsey has been closely studied, the vascular plants in particular as they have been of far greater significance than mosses, lichens and fungi in the development of vegetation.[22]

Mosses and lichens now cover much of the island. During the island's first 20 years, 20 species of plants were observed at one time or another, but only 10 became established in the nutrient-poor sandy soil. As birds began nesting on the island, soil conditions improved, and more vascular plant species were able to survive. In 1998, the first bush was found on the island—a tea-leaved willow (Salix phylicifolia), which can grow to heights of up to 4 metres (13 feet). By 2008, 69 species of plant had been found on Surtsey,[20] of which about 30 had become established. This compares to the approximately 490 species found on mainland Iceland.[20] More species continue to arrive, at a typical rate of roughly 2–5 new species per year.[22]

Bird life

The expansion of bird life on the island has both relied on and helped to advance the spread of plant life. Birds use the plants for nesting material, but also continue to assist in the spreading of seeds, and fertilize the soil with their guano.[23] Birds first began nesting on Surtsey three years after the eruptions ended, with fulmar and guillemot the first species to set up home. Twelve species are now regularly found on the island.[24]

A gull colony has been present since 1984, although gulls were seen briefly on the shores of the new island weeks after it first appeared.[24] The gull colony has been particularly important in developing the plant life on Surtsey,[23][24] and the gulls have had much more of an impact on plant colonisation than other breeding species due to their abundance. An expedition in 2004 found the first evidence of nesting Atlantic puffins,[24] which are abundant in the rest of the archipelago.[25]

As well as providing a home for some species of birds, Surtsey has also been used as a stopping-off point for migrating birds, particularly those en route between Europe and Iceland.[26][27] Species that have been seen briefly on the island include whooper swans, various species of geese, and common ravens. Although Surtsey lies to the west of the main migration routes to Iceland, it has become a more common stopping point as its vegetation has improved.[28] In 2008, the 14th breeding bird species was detected with the discovery of a common raven's nest.[20]

According to a 30 May 2009 report, a golden plover was nesting on the island, with four eggs.[29]

Marine life

Soon after the island's formation, seals were seen around the island. They soon began basking there, particularly on the northern spit, which grew as the waves eroded the island. Seals were found to be breeding on the island in 1983, and a group of up to 70 made the island their breeding spot. Grey seals are more common on the island than harbour seals, but both are now well established.[30] The presence of seals attracts orcas, which are frequently seen in the waters around the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago and now frequent the waters around Surtsey.

On the submarine portion of the island, many marine species are found. Starfish are abundant, as are sea urchins and limpets. The rocks are covered in algae, and seaweed covers much of the submarine slopes of the volcano, with its densest cover between 10 and 20 metres (33 and 66 ft) below sea level.[31]

Other life

Insects arrived on Surtsey soon after its formation, and were first detected in 1964. The original arrivals were flying insects, carried to the island by winds and their own power. Some were believed to have been blown across from as far away as mainland Europe. Later insect life arrived on floating driftwood, and both live animals and carcasses washed up on the island. When a large, grass-covered tussock washed ashore in 1974, scientists took half of it for analysis and discovered 663[clarification needed] land invertebrates, mostly mites and springtails, the great majority of which had survived the crossing.[32]

The establishment of insect life provided some food for birds, and birds in turn helped many species to become established on the island. The bodies of dead birds provide sustenance for carnivorous insects, while the fertilisation of the soil and resulting promotion of plant life provides a viable habitat for herbivorous insects.

The first earthworm was found in a soil sample in 1993, probably carried over from Heimaey by a bird. However, the next year no earthworms were found. Slugs were found in 1998, and appeared to be similar to varieties found in the southern Icelandic mainland. Spiders and beetles have also become established.[33][34]

Human impact

The only significant human impact is a small prefabricated hut which is used by researchers while staying on the island. The hut includes a few bunk beds and a solar power source to drive an emergency radio and other key electronics. There is also an abandoned lighthouse foundation. All visitors check themselves and belongings to ensure no seeds are accidentally introduced by humans to this ecosystem. It is believed that some boys who sneaked over from Heimaey by rowboat planted potatoes, which were promptly dug up once discovered.[20] An improperly managed human defecation resulted in a tomato plant taking root, which was also destroyed.[20] In 2009, a weather station for weather observations and a webcam were installed on Surtsey.[35]

See also

- Geography of Iceland

- List of islands of Iceland

- List of new islands

- List of volcanoes in Iceland

- Volcanism of Iceland

References

- "A visit to the Surtsey Visitor Centre allows you to travel back in time". Icelandmag. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Surtsey Island 50 Percent Original Size, Iceland Review online, 13 August 2013

- Vésteinsson, Árni (2009), "Surveying and charting the Surtsey area from 1964 to 2007", Surtsey Research Progress Report XII: 52 (Figure 11), retrieved 15 August 2014

- Time-Life books, ed. (1986), Folk och länder, Norden, Höganäs: Bokorama, p. 38, ISBN 978-91-7024-256-4

- Decker, Robert; Decker, Barbara (1997), Volcanoes, New York: Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-3174-0

- Sigtryggsson, Hlynur; Sigurðsson, Eiríkur (1966), "Earth Tremors from the Surtsey Eruption 1963–1965: a preliminary survey", Surtsey Research Progress Report II: 131–138, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Malmberg, Svend-Aage (1965), "The temperature effect of the Surtsey eruption: a report on the sea water", Surtsey Research Progress Report I: 6–9, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Þórarinsson, Sigurður (1965), "The Surtsey eruption: Course of events and the development of the new island.", Surtsey Research Progress Report I: 51–55, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Doutreleau, Vanessa (2006), "Surtsey, naissances d'une île", Ethnologie Française (in French), Presses Universitaires de France, XXXVII (3): 421–433, doi:10.3917/ethn.063.0421, ISBN 978-2-13-055455-4, ISSN 0046-2616, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Norrman, John; Erlingsson, Ulf (1992), "The submarine morphology of Surtsey volcanic group", Surtsey Research Progress Report X: 45–56, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Þórarinsson, Sigurður (1966), "The Surtsey eruption: course of events and the development of Surtsey and other new islands", Surtsey Research Progress Report II: 117–123, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Þórarinsson, Sigurður (1967), "The Surtsey eruption: course of events during the year 1966", Surtsey Research Progress Report III: 84–90, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Garvin, J.B.; Williams Jr, R.S.; Frawley, J.J.; Krabill, W.B. (2000), "Volumetric evolution of Surtsey, Iceland, from topographic maps and scanning airborne laser altimetry", Surtsey Research Progress Report XI: 127–134, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Surtsey Topography, NASA, 12 November 1998, archived from the original on 28 January 1999, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Moore, J.G.; Jakobsson, Sveinn; Holmjarn, Josef (1992), "Subsidence of Surtsey volcano, 1967–1991", Bulletin of Volcanology, 55 (1–2): 17–24, Bibcode:1992BVol...55...17M, doi:10.1007/BF00301116, S2CID 128693202

- Jakobssen, Sveinn P. (6 May 2007), Erosion of the Island, The Spurtsey Research Society, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Jakobssen, Sveinn P. (6 May 2007), The Formation of Palagonite Tuffs, The Surtsey Research Society, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Twenty-seven new sites inscribed, UNESCO, retrieved 13 February 2015

- Surtsey Research Society "Colonization of the Land"Accessed: 2015-01-23. (Archived by WebCite® at)

- Blask, Sara (2008), "Iceland's new island is an exclusive club – for scientists only", The Christian Science Monitor (published 24 October 2008)

- Burrows, Colin (1990), Processes of Vegetation Change, Routledge, pp. 124–127, ISBN 978-0-04-580012-4

- The volcano island: Surtsey, Iceland: Plants, Our Beautiful World, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Thornton, Ian; New, Tim (2007), Island Colonization: The Origin and Development of Island Communities, Cambridge University Press, p. 178, ISBN 978-0-521-85484-9

- Petersen, Ævar (6 May 2007), Bird Life on Surtsey, The Surtsey Research Society, retrieved 14 July 2008

- Puffins in Iceland, Iceland on the web, retrieved 14 July 2008

- Surtsey, Iceland, Our Beautiful World, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Friðriksson, Sturla; Magnússon, Borgþór (6 May 2007), Colonization of the Land, The Surtsey Research Society, retrieved 8 July 2008

- The volcano island: Surtsey, Iceland: Birdlife, Our Beautiful World, retrieved 8 July 2008

- New family moves onto Surtsey Island, no parties allowed Archived 14 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine IceNews, 30 May 2009

- Hauksson, Erlingur (1992), "Observations on Seals on Surtsey in the Period 1980–1989" (PDF), Surtsey Research Progress Report X: 31–32, retrieved 14 July 2008

- The volcano Island Surtsey, Iceland: Sealife, Our Beautiful World, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Ólafsson, Erling (1978), "The development of the land-arthropod fauna on Surtsey, Iceland, during 1971–1976 with notes on terrestrial Oligochaeta", Surtsey Research Progress Report VIII: 41–46, retrieved 8 July 2008

- The volcano island: Surtsey, Iceland: Insects, Our Beautiful World, retrieved 8 July 2008

- Sigurðardóttir, Hólmfríður (2000), "Status of collembolans (Collembola) on Surtsey, Iceland, in 1995 and first encounter of earthworms (lumbricidae) in 1993", Surtsey Research XI: 51–55, retrieved 8 July 2008

- "The Surtsey Research Society".

External links

- The Surtsey Research Society

- Weather observations on Surtsey

- Webcam on Surtsey

- Aerial photos, maps and volcanic geology of Surtsey.

- Visit Westman Islands

- Surtsey Topography

- The Surtsey Research Society Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, which administers the island

- A notice from the Environmental & Food Agency declaring Surtsey a protected area (in Icelandic)

- Explore North site illustrates postage stamps.

- Extensive information about plant and bird life on the island

- "Surtsey, Iceland" in Coastal World Heritage Sites, pp 237-242

На других языках

[de] Surtsey

Surtsey [.mw-parser-output .IPA a{text-decoration:none}'sør̥tsɛi] (isländisch für Insel des Surt) ist eine ab dem 14. November 1963 in einer Ausbruchsserie entstandene Vulkaninsel im Atlantischen Ozean, die etwa 30 Kilometer vor der Südküste Islands liegt. Sie ist nach Heimaey die zweitgrößte der Vestmannaeyjar oder Westmännerinseln und stellt den südlichsten Punkt Islands dar.- [en] Surtsey

[es] Surtsey

Surtsey (que en islandés significa «Isla de Surt») es una isla volcánica situada a aproximadamente 32 kilómetros de la costa meridional de Islandia, cerca del archipiélago de Vestmannaeyjar. Constituye el punto más austral del país y se formó a partir de una erupción volcánica que se inició a 130 m por debajo del nivel del mar y emergió a la superficie el 14 de noviembre de 1963.[1] La erupción duró hasta el 5 de junio de 1967, momento en el que la isla alcanzó su tamaño máximo de 2,7 km² (270 ha). Desde entonces la acción erosiva del viento, el agua y el hielo han reducido constantemente su tamaño hasta las 141 ha, medidas en 2008.[2][1][fr] Surtsey

Surtsey (/ˈsʏr̥(t)sˌeiː/[2]) est une île volcanique située au large de la côte méridionale de l'Islande, à l'extrémité sud des îles Vestmann. Elle s'est formée à la suite d'une éruption volcanique qui a commencé à 130 mètres sous le niveau de la mer aux alentours du 10 novembre 1963, a atteint la surface le 14 novembre 1963 et s'est terminée le 5 juin 1967. C'est à cette date que l'île a atteint sa superficie maximale avec 2,65 km2 et sa hauteur maximale avec 173 mètres d'altitude. Depuis, sous l'action érosive du vent et des vagues, l'île a diminué de superficie pour ne mesurer plus que 1,41 km2 en 2008. Elle a perdu aussi en altitude à cause de l'érosion essentiellement maritime, du compactage des couches sédimentaires sous-jacentes et à un moindre degré du réajustement isostatique de la lithosphère.[it] Surtsey

Surtsey (in islandese "isola di Surtr") (pronuncia: ˈsʏr̥(t)sˌeiː) è un'isola vulcanica al largo della costa meridionale dell'Islanda emersa dal mare nel 1963. Situata alla latitudine di 63°17′ N, è il punto più meridionale dell'Islanda[1].[ru] Сюртсей

Сюртсей (исл. Surtsey) — необитаемый остров в Исландии, самая южная точка страны, объект Всемирного природного наследия. Один из объектов группы вулканического комплекса Вестманнаэйяр.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии