geo.wikisort.org - Coast

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India,[4] consists of the southern part of India encompassing the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry, comprising 19.31% of India's area (635,780 km2 or 245,480 sq mi) and 20% of India's population. Covering the southern part of the peninsular Deccan Plateau, South India is bounded by the Bay of Bengal in the east, the Arabian Sea in the west and the Indian Ocean in the south. The geography of the region is diverse with two mountain ranges – the Western and Eastern Ghats – bordering the plateau heartland. The Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, Tungabhadra, Periyar, Bharathappuzha, Pamba, Thamirabarani, Palar and Vaigai rivers are important perennial rivers.

South India | |

|---|---|

Region | |

From Top, left to right: Ross Beach (Andaman), Venkateswara Temple (Andhra Pradesh), Mysore Palace (Karnataka), Backwaters of Alappuzha (Kerala), Bangaram island (Lakshwadeep), Matrimandir (Puducherry), Thiruvalluvar Statue (Tamil Nadu), Charminar (Telangana). | |

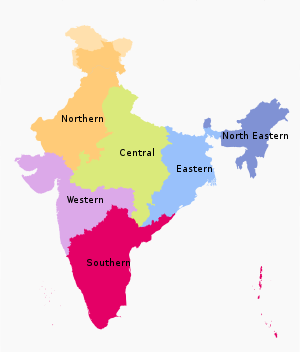

Map of states and union territories in South India | |

| Country | |

| States and union territories | |

| Most populous cities | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 635,780 km2 (245,480 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation (Anamudi) | 2,695 m (8,842 ft) |

| Lowest elevation (Kuttanad) | −2.2 m (−7.2 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 253,051,953 |

| • Density | 400/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | South Indian Dravidian Andhraite Kannadiga Keralite Malayali Laccadivian Pondicherrian Tamilian Telanganite |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Official languages | |

| HDI (2019) | |

| Literacy (2011) | 81.09%[2] |

| Sex ratio (2011) | 986 ♀/1000 ♂[3] |

| Minority languages | |

The majority of the people in South India speak at least one of the four major Dravidian languages: Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam (all 4 of which are among the 6 Classical Languages of India). Some states and union territories also recognize a minority language, such as Deccani Urdu in Telangana,[5] and French in Puducherry. Besides these languages, English is used by both the central and state governments for official communications and is used on all public signboards.

During its history, a number of dynastic kingdoms ruled over parts of South India, and the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent across southern and southeastern Asia affected the history and culture in those regions. Major dynasties established in South India include the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas, Pallavas, Satavahanas, Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Bahmani, Deccan Sultanates, Cochin, Kakatiyas, Kadambas, Hoysalas, Zamorin, Vijayanagara, Maratha, Travancore, Arakkal, and Mysore. Jews, Saint Thomas Christians, Mappila Muslims, and Europeans entered India through the southwestern Malabar Coast of Kerala. Parts of South India were colonized under Portuguese India, French India and the British Raj. The Hyderabad State ruled by the Nizams was the last princely state of India.

South India witnessed sustained growth in per-capita income and population, structural changes in the economy, an increased pace of technological innovation. After experiencing fluctuations in the decades immediately after Indian independence, the economies of South Indian states have registered a higher-than-national-average growth over the past three decades. South India has the largest gross domestic product compared to other regions in India. The South Indian states lead in some socio-economic metrics of India. The HDI in the southern states is high and the economy has undergone growth at a faster rate than in most northern states. Literacy rates in the southern states is higher than the national average, with approximately 81% of the population capable of reading and writing. The fertility rate in South India is 1.9, the lowest of all regions in India.

Etymology

South India is also known as Peninsular India, and has been known by several other names too. The term "Deccan", referring to the area covered by the Deccan Plateau that covers most of peninsular India excluding the coastal areas, is an anglicised form of the Prakrit word dakkhin derived from the Sanskrit word dakshina meaning south.[4] Carnatic, derived from "Karnād" or "Karunād" meaning high country, has also been associated with South India.[6]

History

Historical references

Historical South India has been referred to as Deccan, a prakritic derivative of an ancient term 'Dakshin' or Dakshinapatha. The term had geographical as well as the geopolitical meaning and was mentioned as early as Panini (500 BCE).

Ancient era

Carbon dating shows that ash mounds associated with Neolithic cultures in South India date back to 8000 BCE. Artifacts such as ground stone axes and minor copper objects have been found in the Odisha region. Towards the beginning of 1000 BCE, iron technology spread through the region; however, there does not appear to be a fully developed Bronze Age preceding the Iron Age in South India.[7] The region was in the middle of a trade route that extended from Muziris to Arikamedu linking the Mediterranean to East Asia.[8][9] Trade with Phoenicians, Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Syrians, Jews, and Chinese began during the Sangam period (c. 3rd century BCE to c. 4th century CE).[10] The region was part of the ancient Silk Road connecting the East with the West.[11]

Several dynasties – such as the Cheras of Karuvur, the Pandyas of Madurai, the Cholas of Thanjavur, the Zamorins of Kozhikode, the Travancore royal family of Thiruvananthapuram, the Kingdom of Cochin, the Mushikas of Kannur, the Satavahanas of Amaravati, the Pallavas of Kanchi, the Kadambas of Banavasi, the Western Gangas of Kolar, the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta, the Chalukyas of Badami, the Hoysalas of Belur, and the Kakatiyas of Orugallu – ruled over the region from the 6th century BCE to the 14th century CE. The Vijayanagara Empire, founded in the 14th century CE. was the last Indian dynasty to rule over the region. After repeated invasions from the Sultanate of Delhi and the fall of Vijayanagara empire in 1646, the region was ruled by Deccan Sultanates, the Maratha Empire, and polygars and Nayak governors of the Vijayanagara empire who declared their independence.[12]

Colonial era

The Europeans arrived in the 15th century; and by the middle of the 18th century, the French and the British were involved in a protracted struggle for military control over South India. After the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799 and the end of the Vellore Mutiny in 1806, the British consolidated their power over much of present-day South India, with the exception of French Pondichéry. The British Empire took control of the region from the British East India Company in 1857.[13] During the British colonial rule, the region was divided into the Madras Presidency, Hyderabad State, Mysore, Travancore, Kochi, Jeypore, and a number of other minor princely states. The region played a major role in the Indian independence movement: of the 72 delegates who participated in the first session of the Indian National Congress at Bombay in December 1885, 22 hailed from South India.[14]

Post-independence

After the independence of India in 1947, the region was organised into four states: Madras State, Mysore State, Hyderabad State and Travancore–Cochin.[15] The States Reorganisation Act of 1956 reorganized the states on linguistic lines, resulting in the creation of the new states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.[16][17] As a result of this Act, Madras State retained its name and Kanyakumari district was added to it from the state of Travancore-Cochin.[18] The state was subsequently renamed Tamil Nadu in 1968.[18] Andhra Pradesh was created through the merger of Andhra State with the Telugu-speaking districts of Hyderabad State in 1956.[18] The Marathi-speaking Marathwada region of Hyderabad State was transferred to Bombay State and ceased to be a part of South India. Kerala emerged from the merger of Malabar district and the Kasaragod taluk of South Canara districts of Madras State with Travancore–Cochin.[18] Mysore State was re-organised with the addition of the districts of Bellary and South Canara (excluding Kasaragod taluk[note 1]) and the Kollegal taluk of Coimbatore district from Madras State; the districts of Belgaum, Bijapur, North Canara, and Dharwad from Bombay State; the Kannada-majority districts of Bidar, Raichur, and Gulbarga from the Hyderabad State; and the province of Coorg.[18] Mysore State was renamed as Karnataka in 1973. The Union territory of Puducherry was created in 1954, comprising the previous French enclaves of Pondichérry, Karaikal, Yanam, and Mahé.[19] The Laccadive Islands, which were divided between South Canara and the Malabar districts of Madras State, were united and organised into the union territory of Lakshadweep. Goa was created as a union territory by taking military actions against the Portuguese by the government of India, later it has been declared as a state due to its drastic growth.[20] Telangana was created on 2 June 2014 by bifurcating Andhra Pradesh; and it comprises ten districts of the erstwhile state of Andhra Pradesh.[21][22]

Geography

South India is a peninsula in the shape of an inverted triangle bound by the Arabian Sea on the west, by the Bay of Bengal on the east and the Vindhya and Satpura ranges on the north.[23] The Narmada river flows westwards in the depression between the Vindhya and Satpura ranges, which define the northern spur of the Deccan plateau.[24] The Western Ghats run parallel to the Arabian Sea along the western coast and the narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea forms the Konkan region. The Western Ghats continue south until Kanyakumari.[25][26] The Eastern Ghats run parallel to the Bay of Bengal along the eastern coast and the strip of land between them forms the Coromandel region.[27] Both mountain ranges meet at the Nilgiri mountains. The Nilgiris run in a crescent approximately along the borders of Tamil Nadu with northern Kerala and Karnataka, encompassing the Palakkad and Wayanad hills and the Sathyamangalam ranges, extending to the relatively low-lying hills of the Eastern Ghats on the western portion of the Tamil Nadu–Andhra Pradesh border, forming the Tirupati and Annamalai hills.[28]

The low-lying coral islands of Lakshadweep are situated off the southwestern coast of India. The Andaman and Nicobar islands lie far off the eastern coast. The Palk Strait and the chain of low sandbars and islands known as Rama's Bridge separate the region from Sri Lanka, which lies off the southeastern coast.[29][30] The southernmost tip of mainland India is at Kanyakumari where the Indian Ocean meets the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea.[31]

The Deccan plateau is the elevated region bound by the mountain ranges.[32] The plateau rises to 100 metres (330 ft) in the north and to more than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) in the south, forming a raised triangle within the downward-pointing triangle of the Indian subcontinent's coastline.[33] It also slopes gently from West to East resulting in major rivers arising in the Western Ghats and flowing east into the Bay of Bengal.[34] The volcanic basalt beds of the Deccan were laid down in the massive Deccan Traps eruption, which occurred towards the end of the Cretaceous period, between 67 and 66 million years ago.[35] Layer after layer was formed by the volcanic activity that lasted 30,000 years;[36] and when the volcanoes became extinct, they left a region of highlands with typically vast stretches of flat areas on top like a table.[37] The plateau is watered by the east-flowing Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, and Vaigai rivers. The major tributaries include the Pennar, Tungabhadra, Bhavani, and Thamirabarani rivers.[38]

Climate

The region has a tropical climate and depends on monsoons for rainfall. According to the Köppen climate classification, it has a non-arid climate with minimum mean temperatures of 18 °C (64 °F).[39] The most humid is the tropical monsoon climate characterized by moderate to high year-round temperatures and seasonally heavy rainfall above 2,000 mm (79 in) per year. The tropical climate is experienced in a strip of south-western lowlands abutting the Malabar Coast, the Western Ghats; the islands of Lakshadweep and Andaman and Nicobar are also subject to this climate.[40]

A tropical wet and dry climate, drier than areas with a tropical monsoon climate, prevails over most of the inland peninsular region except for a semi-arid rain shadow east of the Western Ghats. Winter and early summer are long dry periods with temperatures averaging above 18 °C (64 °F); summer is exceedingly hot with temperatures in low-lying areas exceeding 50 °C (122 °F); and the rainy season lasts from June to September, with annual rainfall averaging between 750 and 1,500 mm (30 and 59 in) across the region. Once the dry northeast monsoon begins in September, most precipitation in India falls in Tamil Nadu, leaving other states comparatively dry.[41] A hot semi-arid climate predominates in the land east of the Western Ghats and the Cardamom Hills. The region – which includes Karnataka, inland Tamil Nadu and western Andhra Pradesh – gets between 400 and 750 millimetres (15.7 and 29.5 in) of rainfall annually, with hot summers and dry winters with temperatures around 20–24 °C (68–75 °F). The months between March and May are hot and dry, with mean monthly temperatures hovering around 32 °C (90 °F), with 320 millimetres (13 in) precipitation. Without artificial irrigation, this region is not suitable for agriculture.[42]

The southwest monsoon from June to September accounts for most of the rainfall in the region. The Arabian Sea branch of the southwest monsoon hits the Western Ghats along the coastal state of Kerala and moves northward along the Konkan coast, with precipitation on coastal areas west of the Western Ghats. The lofty Western Ghats prevent the winds from reaching the Deccan Plateau; hence, the leeward region (the region deprived of winds) receives very little rainfall.[43][44] The Bay of Bengal branch of the southwest monsoon heads toward northeast India, picking up moisture from the Bay of Bengal. The Coramandel coast does not receive much rainfall from the southwest monsoon, due to the shape of the land. Tamil Nadu and southeast Andhra Pradesh receive rains from the northeast monsoon.[45] The northeast monsoon takes place from November to early March, when the surface high-pressure system is strongest.[46] The North Indian Ocean tropical cyclones occur throughout the year in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, bringing devastating winds and heavy rainfall.[47][48][49]

Flora and fauna

There is a wide diversity of plants and animals in South India, resulting from its varied climates and geography. Deciduous forests are found along the Western Ghats while tropical dry forests and scrub lands are common in the interior Deccan plateau. The southern Western Ghats have rain forests located at high altitudes called the South Western Ghats montane rain forests, and the Malabar Coast moist forests are found on the coastal plains.[50] The Western Ghats is one of the eight hottest biodiversity hotspots in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[51][52]

Important ecological regions of South India are the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve – located at the conjunction of Karnataka, Kerala and, Tamil Nadu in the Nilgiri Hills – and the Agasthyamala Biosphere Reserve - located at the conjunction of Kerala and, Tamil Nadu in the Agastya Mala hills - and the Cardamom Hills of Western Ghats. Bird sanctuaries – including Thattekad, Kadalundi, Vedanthangal, Ranganathittu, Kumarakom, Neelapattu, and Pulicat – are home to numerous migratory and local birds.[53][54] Lakshadweep has been declared a bird sanctuary by the Wildlife Institute of India.[55] Other protected ecological sites include the mangrove forests of Pichavaram, and the backwaters of Pulicat lake, in Tamil Nadu; and Vembanad, Ashtamudi, Paravur, and Kayamkulam lakes in Kerala. The Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve covers an area of 10,500 km2 of ocean, islands and the adjoining coastline including coral reefs, salt marshes and mangroves. It is home to endangered aquatic species, including dolphins, dugongs, whales and sea cucumbers.[56][57]

South India is home to one of the largest populations of endangered Bengal tigers and Indian elephants in India, being home to one-third of the tiger population and more than half of the elephant population,[58][59] with 14 Project Tiger reserves and 11 Project Elephant reserves.[60][61] Elephant populations are found in eight fragmented sites in the region: in northern Karnataka, along the Western Ghats, in Bhadra–Malnad, in Brahmagiri–Nilgiris–Eastern Ghats, in Nilambur–Silent Valley–Coimbatore, in Anamalai–Parambikulam, in Periyar–Srivilliputhur, and in Agasthyamalai[62] Other threatened and endangered species found in the region include the grizzled giant squirrel,[63] grey slender loris,[64] sloth bear,[65] Nilgiri tahr,[66] Nilgiri langur,[67] lion-tailed macaque,[68] and the Indian leopard.[69]

| Name | Animal | Bird | Tree | Fruit | Flower |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands[70] | Dugong (Dugong dugon) | Andaman wood pigeon (Columba palumboides) | Andaman padauk (Pterocarpus dalbergioides) | Andaman crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia hypoleuca) | |

| Andhra Pradesh[71] | Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra) | Rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri) | Neem (Azadirachta indica) | Mango (Mangifera indica) | Common jasmine (Jasminum officinale) |

| Karnataka[72] | Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Indian roller (Coracias indica) | Sandalwood (Santalum album) | Mango (Mangifera indica) | Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) |

| Kerala[73][74] | Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Great hornbill (Buceros bicornis) | Coconut (Cocos nucifera) | Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | Cana fistula (Cassia fistula) |

| Lakshadweep[75][76] | Butterfly fish (Chaetodon falcula) | Noddy tern (Anous stolidus) | Bread fruit (Artocarpus incisa) | ||

| Puducherry[77] | Indian palm squirrel (Funambulus palmarum) | Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus) | Bael fruit (Aegle marmelos) | Cannonball (Couroupita guianensis) | |

| Tamil Nadu[78][79] | Nilgiri tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) | Emerald dove (Chalcophaps indica) | Palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer) | Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | Glory lily (Gloriosa superba) |

| Telangana[80] | Chital deer (Axis axis) | Indian roller (Coracias indica) | Khejri (Prosopis cineraria) | Mango (Mangifera indica) | Tanner's cassia (Senna auriculata) |

Transport

Road

South India has an extensive road network with 20,573 km (12,783 mi) of National Highways and 46,813 km (29,088 mi) of State Highways. The Golden Quadrilateral connects Chennai with Mumbai via Bangalore, and with Kolkata via Visakhapatnam.[81][82] Bus services are provided by state-run transport corporations, namely the Andhra Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation,[83] Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation,[84] Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation,[85] Telangana State Road Transport Corporation,[86] Kerala State Road Transport Corporation,[87] and Puducherry Road Transport Corporation.[88]

| State | National Highway[89] | State Highway[90] | Motor vehicles per 1000 pop.[91] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | 7,356 km (4,571 mi) | 10,650 km (6,620 mi) | 145 |

| Karnataka | 6,432 km (3,997 mi) | 20,774 km (12,908 mi) | 182 |

| Tamil Nadu | 5,006 km (3,111 mi) | 10,764 km (6,688 mi) | 257 |

| Telangana | 2,635 km (1,637 mi) | 3,152 km (1,959 mi) | N/A |

| Kerala | 1,811 km (1,125 mi) | 4,341 km (2,697 mi) | 198 |

| Andaman and Nicobar | 330 km (210 mi) | 38 km (24 mi) | 152 |

| Puducherry | 64 km (40 mi) | 246 km (153 mi) | 521 |

| Total | 22,635 km (14,065 mi) | 49,965 km (31,047 mi) |

Rail

The Great Southern of India Railway Company was founded in England in 1853 and registered in 1859.[92] Construction of track in the Madras Presidency began in 1859 and the 80 miles (130 km) link from Trichinopoly to Negapatam and a link from Tirur to the Port of Beypore at Kozhikode on the Malabar Coast, which eventually got expanded into the Mangalore-Chennai line via Palakkad Gap were opened in 1861.[93] The Carnatic Railway Company was founded in 1864 and opened a Madras–Arakkonam–Conjeevaram–Katpadi junction line in 1865. These two companies subsequently merged in 1874 to form the South Indian Railway Company.[94] In 1880, the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, established by the British, built a railway network radiating from Madras.[95] In 1879, the Madras Railway constructed a line from Royapuram to Bangalore; and the Maharaja of Mysore established the Mysore State Railway to build an extension from Bangalore to Mysore.[96] In order to get access to the west coast, Malabar region of the country through Port of Quilon, Maharajah Uthram Thirunal of Travancore built the Quilon-Madras rail line jointly with the South Indian Railway Company and the Madras Presidency.[97] The Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway was founded on 1 January 1908 by merging the Madras Railway and the Southern Mahratta Railway.[98][99]

On 14 April 1951, the Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway, the South Indian Railway, and the Mysore State Railway were merged to form the Southern Railway, in the first zone of Indian Railways.[100] The South Central zone was created on 2 October 1966 as the ninth zone of Indian Railways and the South Western zone was created on 1 April 2003.[101] Most of the region is covered by the three zones, with small portions of the coasts covered by East Coast Railway and Konkan Railway, In 2019, the Government of India announced the formation of the South Coast Railway zone in the southeast, with headquarters at Visakhapatnam.[102]

Metro rail is operated by Namma Metro in Bangalore, Chennai Metro in Chennai, Kochi Metro in Kochi and Hyderabad Metro in Hyderabad. Chennai MRTS provides suburban rail services in Chennai and was the first elevated railway line in India.[103] Hyderabad MMTS provides the suburban rail services in the city of Hyderabad.

The Nilgiri Mountain Railway is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[104]

| Sl. No | Name of railway zone[105] | Abbr. | Route length (in km)[106] | Headquarters[105] | Founded[107] | Divisions | Major stations[108] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Southern | SR | 5,098 | Chennai | 14 April 1951 | Chennai,[109] Tiruchirappalli,[110] Madurai,[111] Palakkad,[112] Salem,[113] Thiruvananthapuram[114] | Chennai Central, Chennai Egmore, Chennai Beach, Tambaram, Coimbatore, Ernakulam, Erode, Katpadi, Kollam, Kozhikode, Madurai, Mangalore Central, Palakkad, Salem, Thanjavur, Thiruvananthapuram Central, Thrissur, Tiruchirappalli, Tirunelveli |

| 2. | South Coast | SCoR | 3,496 | Visakhapatnam | 2019 (announced) | Waltair, Vijayawada, Guntakal, Guntur | Visakhapatnam, Guntur, Nellore, Tirupati Main, Vijayawada, Adoni, Guntakal, Rajahmundry, Kakinada Town, Kadapa, Kondapalli |

| 3. | South Central | SCR | 3,127 | Secunderabad | 2 October 1966 | Secunderabad,[115] Hyderabad, Nanded | Secunderabad, Hyderabad, Warangal |

| 4. | South Western | SWR | 3,177 | Hubli | 1 April 2003 | Hubli, Bengaluru, Mysore, Gulbarga[116] | Bengaluru City, Hubli, Mysore |

| 5. | East Coast | ECoR | 2,572 | Bhubaneswar | 1 April 2003 | Khurda Road, Sambalpur | Visakhapatnam, Rayagada, Palasa, Vizianagaram |

| 6. | Konkan | KR | 741 | Navi Mumbai | 26 January 1988 | Karwar, Ratnagiri | Madgaon |

Air

Quilon Aerodrome at Kollam, was established under the kingdom of Travancore in 1920, but it was closed in 1932.[117] In March 1930, a discussion initiated by pilot G. Vlasto led to the founding of the Madras Flying Club, which became a pioneer in pilot training in South India.[118] On 15 October 1932, Indian aviator J. R. D. Tata flew a Puss Moth aircraft carrying mail from Karachi to Juhu aerodrome, Bombay; and the aircraft continued to Madras, piloted by Neville Vincent, a former Royal Air Force pilot and friend of Tata.[119] Kannur had an airstrip used for commercial aviation as early as 1935 when Tata airlines operated weekly flights between Mumbai and Thiruvananthapuram – stopping at Goa and Kannur.[120] Chennai International Airport and Trivandrum International Airport, both inaugurated in 1932 and now managed by the Airport Authority of India, are among the oldest existing airports in South India.

There are 11 international airports, 2 customs airports, 15 domestic airports, and 11 air bases in South India. Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Kochi international airports are amongst the 10 busiest in the country.[121][122][123] Chennai International Airport serves as the Southern Regional Headquarters of the Airports Authority of India, the Southern Region comprising the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, and the union territories of Puducherry and Lakshadweep.[124]

The Southern Air Command of the Indian Air Force is headquartered at Thiruvananthapuram, and the Training Command is headquartered at Bengaluru. The Air Force operates eleven air bases in Southern India including two in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[125] In the region, the Indian Navy operates airbases at Kochi, Arakkonam, Uchipuli, Vizag, Campbell Bay, and Diglipur.[126][127]

| State/UT | International | CustomsNote 1 | Domestic | Military |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Karnataka | 2 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Kerala | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Lakshadweep | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Puducherry | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tamil Nadu | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Telangana | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 12 | 1 | 14 | 16 |

^Note 1 Restricted international airport

| Rank | Name | City | State | IATA Code | Total passengers (2018–19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kempegowda International Airport | Bengaluru | Karnataka | BLR | 33,307,702 |

| 2 | Chennai International Airport | Chennai | Tamil Nadu | MAA | 22,543,822 |

| 3 | Rajiv Gandhi International Airport | Hyderabad | Telangana | HYD | 21,403,972 |

| 4 | Cochin International Airport | Kochi | Kerala | COK | 10,119,825 |

| 5 | Trivandrum International Airport | Thiruvananthapuram | Kerala | TRV | 4,434,459 |

| 6 | Calicut International Airport | Kozhikode | Kerala | CCJ | 3,360,847 |

| 7 | Coimbatore International Airport | Coimbatore | Tamil Nadu | CJB | 3,000,882 |

| 8 | Visakhapatnam International Airport | Visakhapatnam | Andhra Pradesh | VTZ | 2,853,390 |

| 9 | Mangalore International Airport | Mangaluru | Karnataka | IXE | 2,240,664 |

| 10 | Tiruchirappalli International Airport | Tiruchirappalli | Tamil Nadu | TRZ | 1,578,831 |

| 11 | Kannur International Airport | Kannur | Kerala | CNN | |

Water

A total of 89 ports are situated along the southern seacoast: Andaman and Nicobar (23), Kerala (17), Tamil Nadu (15), Andhra Pradesh (12), Karanataka(10), Lakshadweep (10), Pondicherry (2).[128] Major ports include those at Visakhapatnam, Chennai, Mangalore, Tuticorin, Ennore, Kakinada, and Kochi.[129]

| Name | City | State | Cargo Handled (FY2017–18)[130] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Million tonnes | % Change (over previous FY) | |||

| Visakhapatnam Port | Visakhapatnam | Andhra Pradesh | 63.54 | 4.12% ↑ |

| Chennai Port | Chennai | Tamil Nadu | 51.88 | 3.32% ↑ |

| New Mangalore Port | Mangalore | Karnataka | 42.05 | 5.28% ↑ |

| V.O. Chidambaranar Port | Thoothukudi | Tamil Nadu | 36.57 | -4.91% ↓ |

| Kamarajar Port | Chennai | Tamil Nadu | 30.45 | 1.42% ↑ |

| Cochin Port | Kochi | Kerala | 29.14 | 16.52% ↑ |

| Gangavaram Port | Visakhapatnam | Andhra Pradesh | 20.54 | 5.12% ↑ |

| Kakinada Port | Kakinada | Andhra Pradesh | 15.12 | 1.1 ↑ |

The Kerala backwaters are a network of interconnected canals, rivers, lakes, and inlets, a labyrinthine system formed by more than 900 km of waterways. In the midst of this landscape, there are a number of towns and cities, which serve as the starting and endpoints of transportation services and backwater cruises.[131] Vizhinjam International Seaport also called The Port of Trivandrum is a mother port under construction on the Arabian Sea at Vizhinjam in Trivandrum, India. Once completed, it is estimated that this port will handle over 40% of India's transshipments, thereby reducing the country's reliance on ports at Dubai, Colombo, and Singapore.

The Eastern Naval Command and Southern Naval Command of the Indian Navy are headquartered at Visakhapatnam and Kochi, respectively.[132][133] In the region, the Indian Navy has its major operational bases at Visakhapatnam, Chennai, Kochi, Karwar, and Kavaratti.[134][135][136]

Economy

After independence, the economy of South India conformed to a socialist framework, with strict governmental control over private sector participation, foreign trade, and foreign direct investment. From 1960 to 1990, the South Indian economies experienced mixed economic growth. In the 1960s, Kerala achieved above-average growth while Andhra Pradesh's economy declined. Kerala experienced an economic decline in the 1970s while the economies of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh consistently exceeded national average growth rates, due to reform-oriented economic policies.[137] As of March 2015, there are 109 operational Special Economic Zones in South India, which is about 60% of the country's total.[138] As of 2019–20, the total gross domestic product of the region is ₹67 trillion (US$946 billion). Tamil Nadu has the second-highest GDP and is the second-most industrialised state in the country after Maharashtra.[139] With the presence of two major ports, an international airport, and a converging road and rail networks, Chennai is referred to as the "Gateway of South India."[140][141][142][143]

![At 168.91 metres (554.2 ft) height,[144] the Idukki Dam is one of the highest arch dams in Asia.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Idukki_Dam_Reservoir.jpg/220px-Idukki_Dam_Reservoir.jpg)

Over 48% of South India's population is engaged in agriculture, which is largely dependent on seasonal monsoons. Frequent droughts have left farmers debt-ridden, forcing them to sell their livestock and sometimes to commit suicide.[145] Some of the main crops cultivated in South India include paddy, sorghum, pearl millet, pulses, ragi, sugarcane, mangoes, chilli, and cotton. The staple food is rice; the delta regions of Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri are among the top rice producing areas in the country.[138][146] Areca nut, coffee, tea, turmeric and other spices, and rubber are cultivated in the hills, the region accounting for 92% of the total coffee production in India.[138][147][148][149][150] Other major agricultural products include poultry and silk.[151][152]

South India's urban centres are significant contributors to the Indian and global economy. According to the Globalization and World Cities Research Network, Bengaluru, Chennai, and Hyderabad are the South Indian cities most integrated with the global economy. Bengaluru is classified as an alpha world city, while Chennai and Hyderabad are beta world cities.[153]

Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, Coimbatore, Visakhapatnam, and Thiruvananthapuram are amongst the major information technology (IT) hubs of India, with Bengaluru known as the Silicon Valley of India.[154] The presence of these hubs has spurred economic growth and attracted foreign investments and job seekers from other parts of the country.[155] Software exports from South India grossed over ₹640 billion (US$8.0 billion) in fiscal 2005–06.[156]

Salem Steel Plant (SSP), a unit of Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL), is a steel plant involved in the production of stainless steel.[157] It is located along the Salem — Bangalore National Highway 44 in the foothills of Kanjamalai in Salem district, Tamil Nadu, India.[158][159] The plant has an installed capacity of 70,000 tonnes per annum in its cold rolling mill and 3,64,000 tonnes per annum in the hot rolling mill.[157] It also has the country's first stainless steel blanking facility.[160]

Chennai, known as the "Detroit of Asia", accounts for about 35% of India's overall automotive components and automobile output.[161] Coimbatore supplies two-thirds of India's requirements of motors and pumps, and is one of the largest exporters of wet grinders and auto components, as well as jewellery.[162] Andhra Pradesh is emerging as another automobile manufacturing hub.[163]

Another major industry is textiles[164] with the region being home to nearly 60% of the fiber textile mills in India.[165]

Tourism contributes significantly to the GDP of the region, with three states – Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Telangana – among the top 10 states for tourist arrivals, accounting for more than 50% of domestic tourist visits.[166]

| Economic and demographic indicators[167] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | South India | National |

| Gross domestic product (GDP) | ₹67 trillion (US$946 billion) | ₹209.19 trillion (US$2.9 trillion) |

| Net state domestic product (SDP) | ₹29,027 (US$360) | ₹23,222 (US$290) |

| Population below the poverty line | 15.41% | 26.1% |

| Urban population | 32.8% | 27.8% |

| Households with electricity | 98.91% | 88.2% |

| Literacy rate | 81.09% | 74%[168] |

Demographics

As per the 2011 census of India, the estimated population of South India was 252 million, around one fifth of the total population of the country. The region's total fertility rate (TFR) was less than the population replacement level of 2.1 for all states, with Kerala and Tamil Nadu having the lowest TFRs in India at 1.7.[169][170] As a result, from 1981 to 2011 the proportion of the population of South India to India's total population has declined.[171][172] The population density of the region is approximately 463 per square kilometer.[citation needed] Scheduled Castes and Tribes form 18% of the population of the region. Agriculture is the major employer in the region, with 47.5% of the population being involved in agrarian activities.[173] About 60% of the population lives in permanent housing structures.[174] 67.8% of South India has access to tap water, with wells and springs being major sources of water supply.[175]

After experiencing fluctuations in the decades immediately after the independence of India, the economies of South Indian states have, over the past three decades, registered growth higher than the national average. While South Indian states have improved in some of the socio-economic metrics,[167][176] poverty continues to affect the region as it does the rest of the country, although it has considerably decreased over the years. Based on the 2011 census, the HDI in the southern states is high, and the economy has grown at a faster rate than those of most northern states.[177]

As per the 2011 census, the average literacy rate in South India is approximately 80%, considerably higher than the Indian national average of 74%, with Kerala having the highest literacy rate of 93.91%.[178] South India has the highest sex ratio with Kerala and Tamil Nadu being the top two states.[179] The South Indian states rank amongst the top 10 in economic freedom, life expectancy, access to drinking water, house ownership, and TV ownership.[180][181][182][183][184] The poverty rate is at 19% while that in the other Indian states is at 38%. The per capita income is ₹19,531 (US$240), which is more than double of the other Indian states (₹8,951 (US$110)).[185][186] Of the three demographically related targets of the Millennium Development Goals set by the United Nations and expected to be achieved by 2015, Kerala and Tamil Nadu achieved the goals related to improvement of maternal health and of reducing infant mortality and child mortality by 2009.[187][188]

Languages

The largest linguistic group in South India is the Dravidian family of languages, of approximately 73 languages.[190] The major languages spoken include Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam.[191] Tulu is spoken by about 1.5 million people in coastal Kerala and Karnataka; Konkani, an Indo-Aryan language, is spoken by around 0.8 million people in the Konkan coast (Canara) and Kerala; Kodava Takk is spoken by more than half a million people in Kodagu, Mysore, and Bangalore. English is also widely spoken in urban areas of South India.[192] Deccani Urdu is spoken by around 12 million Muslims in southern India.[193][194][195] Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam, Konkani, and Deccani Urdu are listed among the 22 official languages of India as per the Official Languages Act (1963). Tamil was the first language to be granted classical language status by the Government of India in 2004.[196][197] Other major languages declared classical are Kannada (in 2008), Telugu (in 2008), and Malayalam (in 2013)[198][199] These four languages have literary outputs larger than other literary languages of India.[200]

| S.No. | Language | Number of speakers[201] | States and union territories where official |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Telugu | 74,002,856 | Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Puducherry |

| 2 | Tamil | 60,793,814 | Tamil Nadu, Puducherry |

| 3 | Kannada | 43,706,512 | Karnataka |

| 4 | Malayalam | 34,838,319 | Kerala, Lakshadweep, Mahé |

| 5 | Deccani Urdu | 12 – 13 million | Telangana |

| 6 | Tulu | 1,846,427 | Dakshina Kannada, Udupi district, Kasargod district |

| 7 | Konkani | 800,000+ | Uttara Kannada (Karnataka), Dakshina Kannada (Karnataka), Udupi Karnataka, Goa. |

| 8 | Kodava Takk | Kodagu district (Karnataka) |

Religion

Evidence of prehistoric religion in South India comes from scattered Mesolithic rock paintings depicting dances and rituals, such as the Kupgal petroglyphs of eastern Karnataka, at Stone Age sites.[202]

Hinduism is the major religion today in South India, with about 84% of the population adhering to it, which is often regarded as the oldest religion in the world, tracing its roots to prehistoric times in India.[203] Its spiritual traditions include both the Shaivite and Vaishnavite branches of Hinduism, although Buddhist and Jain philosophies were influential several centuries earlier.[204] Ayyavazhi has spread significantly across the southern parts of South India.[205][206] Shaiva Siddhanta philosophy is prominent among many communities.[207]

Shaivism developed as an amalgam of pre-Vedic religions and traditions derived from the southern Tamil Dravidian Shaiva Siddhanta traditions and philosophies, which were assimilated in the non-Vedic Shiva-tradition. The religious history of South India is influenced by Hinduism quite notably during the medieval century. The twelve Alvars (saint-poets of Vaishnavite tradition) and sixty-three Nayanars (saint poets of Shaivite tradition) are regarded as exponents of the bhakti tradition of Hinduism in South India. Most of them came from the Tamil region and the last of them lived in the 9th century CE.

About 11% of the population follow Islam, which was introduced to South India in the early 7th century by Arab traders on the Malabar Coast, and spread during the rule of the Deccan Sultanates, from the 17th to 18th centuries. Muslims of Arab descent in Kerala are called Jonaka Mappila.[208]

About 4% follow Christianity.[209] According to tradition, Christianity was introduced to South India by Thomas the Apostle, who visited Muziris in Kerala in 52 CE and proselytized natives, who are called Nazrani Mappila.[210][211]

Kerala is also home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, who are supposed to have arrived on the Malabar coast during the reign of King Solomon.[212][213]

Administration

South India consists of the five southern Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, as well as the union territories of Puducherry, and Lakshadweep.[214] Puducherry and the five states each have an elected state government, while Lakshadweep is centrally administered by the president of India.[215][216] Each state is headed by a Governor who is appointed by the President of India and who names the leader of the state legislature's ruling party or coalition as chief minister, who is the head of the state government.[217][218]

Each state or territory is further divided into districts, which are further subdivided into revenue divisions and taluks / Mandals or tehsils.[219][220] Local bodies govern respective cities, towns, and villages, along with an elected mayor, municipal chairman, or panchayat chairman, respectively.[220]

States

| S. No. | Name | ISO 3166-2 code[221][222] | Date of formation[18] | Population | Area (km2)[223] |

Official language(s)[224] |

Capital | Population density (per km2)[223] |

Sex Ratio[223] | Literacy Rate (%)[178] | % of urban population[225] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andhra Pradesh | AP | 1 Oct 1953 | 49,506,799[226] | 162,968[226] | Telugu, English | Amaravati | 308[226] | 996[226] | 67.41[227] | 29.4[226] |

| 2 | Karnataka | KA | 1 Nov 1956 | 61,095,297 | 191,791 | Kannada, English | Bengaluru | 319 | 973 | 75.60 | 38.67 |

| 3 | Kerala | KL | 1 Nov 1956 | 33,406,061 | 38,863 | Malayalam, English | Thiruvananthapuram | 860 | 1084 | 94.00 | 47.72 |

| 4 | Tamil Nadu | TN | 26 Jan 1950 | 72,147,030 | 130,058 | Tamil, English | Chennai | 555 | 996 | 80.33 | 48.40 |

| 5 | Telangana | TG | 2 Jun 2014[228] | 35,193,978[228] | 112,077[228] | Telugu, Deccani Urdu | Hyderabad | 307[229] | 988[228] | 66.50[229] | 38.7[228] |

- ^Note 1 Andhra Pradesh was divided into two states, Telangana and a residual Andhra Pradesh on 2 June 2014.[230][231][232] Hyderabad, located entirely within the borders of Telangana, is to serve as joint capital for both states for a period of time not exceeding ten years.[233]

Union territories

| S.No. | Name | ISO 3166-2 code[221][222] | Population | Area (km2)[223] |

Official language[224] |

Capital | Population density (per km2)[223] |

Sex Ratio[223] | Literacy Rate(%)[178] | % of urban population[225] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lakshadweep | LD | 64,473 | 30 | English, Malayalam | Kavaratti | 2,013 | 946 | 92.28 | 78.07 |

| 2 | Puducherry | PY | 1,247,953 | 490 | Tamil, English | Puducherry | 2,598 | 1037 | 86.55 | 68.33 |

Legislative representation

South India elects 132 members to the Lok Sabha, accounting for roughly one-fourth of the total strength.[234] The region is allocated 58 seats in the Rajya Sabha, out of the total of 245.[235]

The state legislatures of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Puducherry are unicameral, while Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Telangana have bicameral legislatures.[236][237] States with bicameral legislatures have an upper house (Legislative Council) with members not more than one-third the size of the Assembly. State legislatures elect members for terms of five years.[220] Governors may suspend or dissolve assemblies and can administer when no party is able to form a government.[220]

| State/UT | Lok Sabha[234] | Rajya Sabha[235] | Saasana Sabha/Vidhan Sabha[236] | Governor/Lieutenant Governor | Chief Minister |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | 25 | 11 | 175 | Biswabhusan Harichandan | Y. S. Jaganmohan Reddy |

| Karnataka | 28 | 12 | 224 | Thawar Chand Gehlot | Basavaraj Bommai |

| Kerala | 20 | 9 | 140 | Arif Mohammad Khan | Pinarayi Vijayan |

| Lakshadweep | 1 | N/A | N/A | H. Rajesh Prasad | N/A |

| Puducherry | 1 | 1 | 30 | Tamilisai Soundararajan | N. Rangaswamy |

| Tamil Nadu | 39 | 18 | 234 | R. N. Ravi | M. K. Stalin |

| Telangana | 17 | 7 | 119 | Tamilisai Soundararajan | K. Chandrashekar Rao |

| Total | 132 | 58 | 922 |

Politics

Politics in South India is characterized by a mix of regional and national political parties. The Justice Party and Swaraj Party were the two major parties in the erstwhile Madras Presidency.[238] The Justice Party eventually lost the 1937 elections to the Indian National Congress, and Chakravarti Rajagopalachari became the Chief Minister of the Madras Presidency.[238]

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Self-Respect Movement, spearheaded by Theagaroya Chetty and E. V. Ramaswamy (commonly known as Periyar), emerged in the Madras Presidency.[239] In 1944, Periyar transformed the party into a social organisation, renaming the party Dravidar Kazhagam, and withdrew from electoral politics. The initial aim was the secession of Dravida Nadu from the rest of India upon Indian independence. After independence, C. N. Annadurai, a follower of Periyar, formed the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in 1948. The Anti-Hindi agitations of Tamil Nadu led to the rise of Dravidian parties that formed Tamil Nadu's first government, in 1967. In 1972, a split in the DMK resulted in the formation of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) led by M. G. Ramachandran. Dravidian parties continue to dominate Tamil Nadu electoral politics, the national parties usually aligning as junior partners to the major Dravidian parties, AIADMK and DMK.[240][241]

Indian National Congress dominated the political scene in Tamil Nadu in the 1950s and 1960s under the leadership of K. Kamaraj, who led the party after the death of Jawaharlal Nehru and ensured the selection of Prime Ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi.[242] Congress continues to be a major party in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Kerala. The party ruled with minimal opposition for 30 years in Andhra Pradesh, before the formation of the Telugu Desam Party by Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao in 1982.[243] Two prominent coalitions in Kerala are the United Democratic Front, led by the Indian National Congress, and the Left Democratic Front, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). For the past fifty years, these two coalitions have been alternately in power; and E. M. S. Namboodiripad, the first elected chief minister of Kerala in 1957, is credited as the leader of the first democratically elected communist government in the world.[244][245] The Bharatiya Janata Party and Janata Dal (Secular) are significant parties in Karnataka.[246]

C. Rajagopalachari, the first Indian Governor General of India post independence, was from South India. The region has produced six Indian presidents, namely, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,[247] V. V. Giri,[248] Neelam Sanjiva Reddy,[249] R. Venkataraman,[250] K. R. Narayanan,[251] and APJ Abdul Kalam.[252] Prime ministers P. V. Narasimha Rao and H. D. Deve Gowda were from the region.[253]

Culture and heritage

Clothing

South Indian women traditionally wear a sari, a garment that consists of a drape varying from 5 yards (4.6 m) to 9 yards (8.2 m) in length and 2 feet (0.61 m) to 4 feet (1.2 m) in breadth that is typically wrapped around the waist, with one end draped over the shoulder, baring the midriff, as according to Indian philosophy, the navel is considered as the source of life and creativity.[254][255] Ancient Tamil poetry, such as the Silappadhikaram, describes women in exquisite drapery or sari.[256] Madisar is a typical style worn by Brahmin women from Tamil Nadu.[257] Women wear colourful silk sarees on special occasions such as marriages.[258]

The men wear a dhoti, a 4.5 metres (15 ft) long, white rectangular piece of non-stitched cloth often bordered in brightly coloured stripes. It is usually wrapped around the waist and the legs and knotted at the waist.[259] A colourful lungi with typical batik patterns is the most common form of male attire in the countryside.[260]

People in urban areas generally wear tailored clothing, and western dress is popular. Western-style school uniforms are worn by both boys and girls in schools, even in rural areas.[260]

Calico, a plain-woven textile made from unbleached, and often not fully processed, cotton, was originated at Calicut (Kozhikode), from which the name of the textile came, in South India, now Kerala, during the 11th century,[261] where the cloth was known as Chaliyan.[262] The raw fabric was dyed and printed in bright hues, and calico prints later became popular in the Europe.[263]

Cuisine

Rice is the diet staple, while fish is an integral component of coastal South Indian meals.[264] Coconut and spices are used extensively in South Indian cuisine. The region has a rich cuisine involving both traditional non-vegetarian and vegetarian dishes comprising rice, legumes, and lentils. Its distinct aroma and flavour is achieved by the blending of flavourings and spices, including curry leaves, mustard seeds, coriander, ginger, garlic, chili, pepper, cinnamon, cloves, green cardamom, cumin, nutmeg, coconut, and rosewater.[265][266]

The traditional way of eating a meal involves being seated on the floor, having the food served on a banana leaf,[267] and using clean fingers of the right hand to take the food into the mouth.[268] After the meal, the fingers are washed; the easily degradable banana leaf is discarded or becomes fodder for cattle.[269] Eating on banana leaves is a custom thousands of years old, imparts a unique flavor to the food, and is considered healthy.[270]

Idli, dosa, uthappam, Pesarattu, appam, pongal, and paniyaram are popular breakfast dishes in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala.[271][272] Rice is served with sambar, rasam, and poriyal for lunch. Andhra cuisine is characterised by pickles and spicy curries.[273] Famous dishes are Pesarattu, Ulava charu, Bobbatlu, Pootharekulu, and Gongura. Chettinad cuisine is famous for its non-vegetarian items, and Hyderabadi cuisine is popular for its biryani.[274] Neer dosa, Chitranna, Ragi mudde, Maddur vada, Mysore pak, Obbattu, Bisi Bele Bath, Mangalore buns, Kesari bat, Akki rotti and Dharwad pedha are famous cuisines of Karnataka.[275] Udupi Cuisine, which originates from Udupi located in the Coastal Kanara region of Karnataka is famous for its vegetarian dishes.[276]

Coconut is native to Southern India and spread to Europe, Arabia, and Persia through the southwestern Malabar Coast of South India over the centuries. Coconut of Indian origin was brought to the Americas by Portuguese merchants. Black pepper is also native to the Malabar Coast[277][278] of India, and the Malabar pepper is extensively cultivated there. During classical era, Phoenicians, Greeks, Egyptians, Romans, and Chinese were attracted by the spices including Cinnamon and Black pepper from the ancient port of Muziris in the southwestern coast of India.[279][280]

During Middle Ages prior to the Age of Discovery which began with the end of the 15th century CE, the kingdom of Calicut (Kozhikode) on Malabar Coast was the centre of Indian pepper exports to the Red Sea and Europe at this time[281] with Egyptian and Arab traders being particularly active. The Thalassery cuisine, a style of cuisine originated in the Northern Kerala over centuries, makes use of such spices.

Music and dance

The traditional music of South India is known as Carnatic music, which includes rhythmic and structured music by composers such as Purandara Dasa, Kanaka Dasa, Tyagayya, Annamacharya, Baktha Ramadasu, Muthuswami Dikshitar, Shyama Shastri, Kshetrayya, Mysore Vasudevachar, and Swathi Thirunal.[282] The main instrument that is used in South Indian Hindu temples is the nadaswaram, a reed instrument that is often accompanied by the thavil, a type of drum instrument.[283]

South India is home to several distinct dance forms such as Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi, Andhra Natyam, Kathakali, Kerala Natanam, Koodiyattam, Margamkali, Mohiniaattam, Oppana, Ottamthullal, Theyyam, Vilasini Natyam, and Yakshagana.[284][285][286][287][288] The dance, clothing, and sculptures of South India exemplify the beauty of the body and motherhood.[254][289][290][291][292]

Cinema

Films done in regional languages are prevalent in South India, with several regional cinemas being recognized: Kannada cinema (Karnataka), Malayalam cinema (Kerala), Tamil cinema (Tamil Nadu), and Telugu cinema (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana). The first silent film in South India, Keechaka Vadham, was made by R. Nataraja Mudaliar in 1916.[293] Mudaliar also established Madras's first film studio.[294] The first Tamil talkie, Kalidas, was released on 31 October 1931, barely seven months after India's first talking picture, Alam Ara.[295]

Swamikannu Vincent built the first cinema studio of South India, at Coimbatore, introducing the "tent cinema", which he first established in Madras and which was known as "Edison's Grand Cinemamegaphone".[296] Filmmakers K Balachandar, Balu Mahendra, Bharathiraaja, and Mani Ratnam in Tamil cinema; Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Shaji N. Karun, John Abraham, and G. Aravindan in Malayalam cinema; Girish Kasaravalli , Girish Karnad and P. Sheshadri in Kannada cinema; and K. N. T. Sastry and B. Narsing Rao in Telugu cinema produced realistic cinema in parallel with each other throughout the 1970s.[297]

South Indian cinema has also had an influence on politics of Tamil Nadu.[298] Prominent film personalities such as C N Annadurai, M G Ramachandran, M Karunanidhi, N. T. Rama Rao, and Jayalalithaa have become chief ministers of South Indian states.[299] As of 2014, South Indian film industries contribute to 53% of the total films produced in India.[300]

| Feature films certified by the Central Board of Film Certification (2019)[301] | |

|---|---|

| Language | No. of films |

| Telugu | 281 |

| Tamil | 254 |

| Malayalam | 219 |

| Kannada | 336 |

| Tulu | 16 |

| Konkani | 10 |

| Total | 1116 |

Literature

South India has an independent literary tradition dating back over 2500 years. The first known literature of South India is the poetic Sangam literature, which was written in Tamil 2500 to 2100 years ago. Tamil literature was composed in three successive poetic assemblies known as Tamil Sangams, the earliest of which, according to ancient tradition, were held on a now vanished continent far to the south of India.[302] This Tamil literature includes the oldest grammatical treatise, Tholkappiyam, and the epics Silappatikaram and Manimekalai.[303] References to Kannada literature appear from the fourth century CE.[304][305] Telugu literature inscriptions. Poets such as Annamacharya made many contributions to this literature.[306] A distinct Malayalam literature came about in the 13th century.[307]

Architecture

South India has two distinct styles of rock architecture, the Dravidian style of Tamil Nadu and the Vesara style of Karnataka.[308]

Koil, Hindu temples of the Dravidian style, consist of porches or mantapas preceding the door leading to the sanctum. Monumental, ornate gate-pyramids, or gopurams – each topped by a kalasam, or stone finial – are the principal features in the quadrangular enclosures that surround the more notable temples[309][310] along with pillared halls. A South Indian temple typically has a water reservoir called the Kalyani or Pushkarni.[311]

The origins of the gopuram can be traced back to early structures of the Pallavas. Under the Pandya rulers in the twelfth century, gateways had become the dominant feature of a temple's outer appearance, eventually overshadowing the inner sanctuary which became obscured from view by the gopuram's colossal size.[312][313]

The Architecture of Kerala is a unique architecture that emerged in the southwestern part of India, which is in its striking contrast to Dravidian architecture, which is normally practised in other parts of South India.[314] It has been performed/followed according to Indian Vedic architectural science (Vastu Shastra).[314]

Notes

- Taluk is a smaller administrative division than a district.

References

- "In the land of many tongues, Hindi can't be lingua franca". Deccan Chronicle. 9 June 2019.

- "Literacy Survey, India (2017–18)". Firstpost. 8 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Census 2011 (Final Data) – Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Yule, Henry; Burnell, A. C. (13 June 2013). Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-164583-9.

- "Urdu is second official language in Telangana as state passes Bill". The News Minute. 17 November 2017.

- "Origins of the word 'Carnatic' in the Hobson Jobson Dictionary". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- Agarwal, D.P. (2006). Urban Origins in India (PDF). Uppsala University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2006.

- Schoff, Wilfred (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel And Trade In The Indian Ocean By A Merchant Of The First Century. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-81-215-0699-1.

- J. Innes, Miller (1998) [1969]. The Spice Trade of The Roman Empire: 29 B.C. to A.D. 641. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814264-5.

- Landstrom, Bjorn (1964). The Quest for India. Allwin and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-910016-9.

- Elisseeff, Vadime (2001). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. UNESCO Publishing / Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-92-3-103652-1.

- "They administered our region". The Hindu. 4 June 2007. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1 March 2000). Great Mutiny: India 1857. Penguin. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-14-004752-3.

- Indian National Evolution: A Brief Survey of the Origin and Progress of the Indian National Congress and the Growth of Indian Nationalism. Cornell University Press. 22 September 2009. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-112-45184-3.

- "Article 1". Constitution of India. Law Ministry, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Reorganisation of states" (PDF). Economic Weekly. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Seventh Amendment". Indiacode.nic.in. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "States Reorganisation Act, 1956" (PDF). indiaenvironmentportal.org.in. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Reorganisation of states" (PDF). Economic Weekly. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Poddar, Prem (2 July 2008). Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures - Continental Europe and its Empires. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3027-1.

- "The Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2014" (PDF). Ministry of law and justice, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Telangana bill passed by upper house". Times of India. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Balfour, Edward (1885). The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial Industrial, and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures. Bernard Quaritch. pp. 1017–1018. ASIN B00IQKGW1M.

- Outram, James (1853). A few brief Memoranda of some of the public services rendered by Lieut.-Colonel Outram, C. B. Smith Elder and Company. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-173-60712-8.

- Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; Da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–858. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..853M. doi:10.1038/35002501. PMID 10706275. S2CID 4414279. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "UN designates Western Ghats as world heritage site". The Times of India. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Eparchaean Unconformity, Tirumala Ghat section". Geological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- Eagan, J. S. C (1916). The Nilgiri Guide And Directory. Chennai: S.P.C.K. Press. ISBN 978-1-149-48220-9.

- "Adam's bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "Map of Sri Lanka with Palk Strait and Palk Bay" (PDF). UN. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "Kanyakumari alias Cape Comorin". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Dr. Jadoan, Atar Singh (September 2001). Military Geography of South-East Asia. India: Anmol Publications. ISBN 81-261-1008-2.

- "The Deccan Peninsula". Sanctuary Asia. 5 January 2001. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006.

- "Eastern Deccan Plateau Moist Forests". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- "What really killed the dinosaurs?". MIT News Office. 11 December 2014.

- Geological Society of America (10 August 2005). "India's Smoking Gun: Dino-killing Eruptions". ScienceDaily.

- "Deccan Plateau". Britannica. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Pullaiah, Thammineni; Rao, D. Muralidhara; Sri Ramamurthy, K. (1 April 2002). Flora of Eastern Ghats: Hill Ranges of South East India. Regency Publications. ISBN 978-81-87498-20-9.

- McKnight, Tom L; Hess, Darrel (2000). "Climate Zones and Types: The Köppen System". Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 205–211. ISBN 0-13-020263-0.

- Chouhan, T. S. (1992). Desertification in the World and Its Control. Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7233-043-9.

- "India's heatwave tragedy". BBC News. 17 May 2002. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Caviedes, C. N. (18 September 2001). El Niño in History: Storming Through the Ages (1st ed.). University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-2099-0.

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2005.

- "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2005.

- "North East Monsoon". IMD. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Rohli, Robert V.; Vega, Anthony J. (2007). Climatology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7637-3828-0.

- Annual frequency of cyclonic disturbances over the Bay of Bengal (BOB), Arabian Sea (AS) and land surface of India (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "hurricane". Oxford dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "The only difference between a hurricane, a cyclone, and a typhoon is the location where the storm occurs". NOAA. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "Indo-Malayan Terrestrial Ecoregions". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 April 2006.

- "Western Ghats". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Lewis, Clara (3 July 2007). "39 sites in Western Ghats get world heritage status". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Baker, H.R.; Inglis, Chas. M. (1930). The birds of southern India, including Madras, Malabar, Travancore, Cochin, Coorg and Mysore. Chennai: Superintendent, Government Press.

- Grimmett, Richard; Inskipp, Tim (30 November 2005). Birds of Southern India. A&C Black.

- "List of proposals for protected areas" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Sacratees, J.; Karthigarani, R. (2008). Environment impact assessment. APH Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-313-0407-5.

- "Conservation and Sustainable-use of the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve's Coastal Biodiversity". New York. 1994. Archived from the original (doc) on 16 June 2007.

- "India's tiger population rises". Deccan Chronicle. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Elephant Census 2005" (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Forests. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2003.

- Panwar, H. S. (1987). Project Tiger: The reserves, the tigers, and their future. Noyes Publications, Park Ridge, N.J. pp. 110–117. ISBN 9780815511335.

- "Project Elephant Status". Times of India. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Sukumar, R (1993). The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43758-X.

- "Grizzled Squirrel Wildlife Sanctuary". Wild Biodiversity. TamilNadu Forest Department. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Singh, M.; Lindburg, D.G.; Udhayan, A.; Kumar, M.A.; Kumara, H.N. (1999). Status survey of slender loris Loris tardigradus lydekkerianus. Oryx. pp. 31–37.

- Kottur, Samad (2012). Daroji-an ecological destination. Drongo. ISBN 978-93-5087-269-7.

- "Nilgiri tahr population over 3,000: WWF-India". The Hindu. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Malviya, M.; Srivastav, A.; Nigam, P.; Tyagi, P.C. (2011). "Indian National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii)" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Singh, M.; Kumar, A.; Kumara, H.N. (2020). "Macaca silenus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T12559A17951402. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12559A17951402.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Stein, A.B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro-Garcia, S.; Kamler, J.F.; Laguardia, A.; Khorozyan, I.; Ghoddousi, A. (2020). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T15954A163991139. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T15954A163991139.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "State Bird/Animal/Tree". Department of Environment & Forest, Andaman & Nicobar Administration. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- "Symbols of AP". andhrabulletin.in. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "Symbols of Karnataka". Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "Symbols of Kerala". Government of India. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Symbols of Kerala". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Symbols of Lakshadweep". Government of India. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Symbols of Lakshadweep" (PDF). Government of Lakshadweep. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Puducherry comes out with list of State symbols". The Hindu. 21 April 2007. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "Symbols of Tamil Nadu". Government of India. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Symbols of Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Telangana symbols". Government of Telangana. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- "Govt declares Golden Quadrilateral complete". Indian Express. 7 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "National Highways Development Project Map". National Highways Institute of India. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Profile, APSRTC". Government of Andhra Pradesh. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "About TNSTC". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "History of KSRTC". Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Krishnamoorthy, Suresh (16 May 2014). "It will be TGSRTC from June 2". The Hindu. Hyderabad. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "KSRTC Directory". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Nair, Rajesh (22 September 2009). "PRTC set for Revival". The Hindu. Puducherry. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- List of highways by state (Report). NHAI. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- Basic Road Statistics of India 2014 (Report). Ministry of Road Transport & Highways. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- Road Transport Yearbook 2011–2012 (Report). Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India. 2012. p. 115. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Indian Tramway Limited". Herepath's Railway and Commercial Journal. 32 (1595): 3. 1 January 1870.

- "'Lifeline' of Malabar turns 125". www.thehindu.com. 29 December 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Always the second station". The Hindu. 3 July 2006. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Rungta, Shyam (1970). The Rise of Business Corporations in India, 1851–1900. Cambridge U.P. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-07354-7.

- "Origin and development of Southern Railway" (PDF). Indian Railways. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Kollam-Sengottai train service likely from May". The Hindu. 21 December 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Raychaudhuri, Tapan; Habib, Irfan (1982). The Cambridge Economic History of India, Vol 2. Orient Blackswan. p. 755. ISBN 978-81-250-2731-7.

- "Third oldest railway station in country set to turn 156". Indian Railways. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Evolution of Indian Railways-Historical Background". Ministry of Railways. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "About Us". South Central Railway. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- "South East Coast Railway could be the New Railway Zone for Andhra Pradesh – RailNews Media India Ltd". Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Sreevatsan, Ajai (10 August 2010). "Metro Rail may take over MRTS". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- "Nilgiri Mountain Railway". IRCTC. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- "Zones & Divisions of Indian Railways". Indian Railways. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Indian Railways Year Book 2009–10 (PDF). Indian Railways. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Introduction to Indian Railways & Rail Budget formulation" (PDF). International centre for Environmental Audit, Government of India. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Top 100 Booking Stations of Indian Railways". Indian Railways. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Chennai Railway Division". Railway Board. Southern Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Tiruchirappalli Railway Division". Railway Board. Southern Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Madurai Railway Division". Railway Board. Southern Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Palakkad Railway Division". Railway Board. Southern Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Salem Railway Division". Railway Board. Southern Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Thiruvananthapuram Railway Division". Railway Board. Southern Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Secunderabad Railway Division". Railway Board. South Central Railway zone. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "New railway division in Gulbarga to be under SWR". The Hindu. 6 March 2014. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- "Aviation school proposal evokes mixed response". The Hindu. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Ayyappan, V. (21 August 2009). "When Good Old Madras Took Wing". Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- "How Maharaja got his wings". Tata Sons. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Sudhakaran, P. "Kannur flew, way before its first airport". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- "Traffic Statistics-2015(April–September)" (PDF). AAI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "Aircraft movements-2015" (PDF). AAI. Retrieved 26 October 2015. [permanent dead link]

- "Cargo Statistics-2015" (PDF). AAI. Retrieved 26 October 2015. [permanent dead link]

- "Regional Headquarters of AAI". Airports Authority of India. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Indian Air Force Commands". Indian Air Force. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- "Organisation of Southern Naval Command". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "ENC Authorities & Units". Indian Navy. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- List of ports (Report). Government of India. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Ports Report" (PDF). Indian Ports Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Traffic handled at major ports (Report). Indian Ports Association. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Evaleigh, Mark (15 January 2016). "Backwater cruises and ancient cures in Kerala, India's southern, sun-drenched state". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- Rao, Kamalakara (14 June 2014). "Vizag based Eastern naval command". Times of India. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "Southern naval command". Indian Navy. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "INS Kadamba". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- "India set to drop anchor off China". Deccan Chronicle. 26 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- "Navy commissions full-scale station in Lakshadweep". The Hindu. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Krishna, K.L. (September 2004). "Economic Growth in Indian States" (PDF). ICRIER. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "Special Economic Zones" (PDF). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) at Current Prices" (PDF). Planning Commission Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2014.

- Mohan, Vishnu (5 October 2020). "Scorching hot during summer and unbelievably crowded, the modern city of Chennai dipped in traditions from its Madras days never fails to surprise a traveller". Outlook Traveller. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- Vikas, S. V. (27 September 2018). "World Tourism Day 2018: Significance, theme and why it is observed". One India. New Delhi. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Grover, Amar (17 September 2019). "Chennai unwrapped: Why the city is the great international gateway to South India". The National. Chennai. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- Sharma, Reetu (23 August 2014). "Chennai turns 375: Things you should know about 'Gateway to South India'". One India. Chennai. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "Idukki Arch Dam". GOVERNMENT OF KERALA. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Farooq, Omer (3 June 2004). "Suicide spree on India's farms". BBC News. Retrieved 10 April 2006.

- "India: A Country Study: Crop Output". Library of Congress, Washington D.C. September 1995. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Yeboah, Salomey (8 March 2005). "Value Addition to Coffee in India". Cornell Education. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2005.

- "Production of Spice by countries". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Possibilities for improving vehicular traffic flow explored". The Hindu. 8 September 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Turmeric at an all-time high price". The Economic Times. 29 December 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Sericulture note". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Tamil Nadu Poultry Industry Seeks Export Concessions". Financial Express. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2020". www.lboro.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

-

- Canton, Naomi (6 December 2012). "How the 'Silicon Valley of India' is bridging the digital divide". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Rai, Saritha (20 March 2006). "Is the Next Silicon Valley Taking Root in Bangalore?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- Vaidyanathan, Rajini (5 November 2012). "Can the 'American Dream' be reversed in India?". BBC World News. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- "Maharashtra tops FDI equity inflows". Business Standard. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "TN software exports clock 32 pc growth". The Hindu Business Line. 7 May 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- "Salem Steel Plant | SAIL". sail.co.in. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "PROFILE OF SALEM STEEL PLANT (SSP)" (PDF). sg.inflibnet.ac.in. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- M, Prakash; M, Manickam (2014). "A Salem Steel plant an Overview". Research Journal of Commerce and Behavioural Science. The International Journal Research Publications. 3: 8. ISSN 2251-1547.

- Dutta, Indrani (12 July 2010). "Salem Steel's expansion set to be completed by September". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Madras, the Detroit of South Asia". Rediff. 30 April 2004. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "India's Gems and Jewellery Market is Glittering". Resource Investor. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "Subramanyam Javvadi: 'Eight auto majors are looking at Andhra Pradesh as their base for operations.'". Autocar Professional. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Lok Sabha Elections 2014: Erode has potential to become a textile heaven says Narendra Modi". DNA India. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "State wise number of cotton mills" (PDF). Confederation of Textile Industry. Retrieved 23 January 2016. [permanent dead link]

- "India Tourism Statistics at a Glance" (PDF). Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Also A Head For Numbers". Outlook. 16 July 2007. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2015.