- Artist's impression of the Thimble Tickle specimen, from Charles Holder's Marvels of Animal Life (1885)[80]

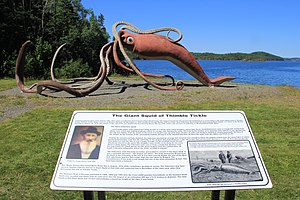

- The "life-sized" concrete and metal sculpture of the Thimble Tickle giant squid, Glovers Harbour (July 2017)

- Sculpture with accompanying information plaque detailing the specimen's history and recognition by Guinness

geo.wikisort.org - Sea

Glovers Harbour[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈɡloʊ.vərz/ GLOH-verz[17][18]), formerly known as Thimble Tickle(s), is an unincorporated community and harbour in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.[5][6][8][19] It is located in Notre Dame Bay on the northern coast of the island of Newfoundland. As a local service district, it is led by an elected committee that is responsible for the delivery of certain essential services. It is delineated as a designated place for statistical purposes.

Glovers Harbour

Thimble Tickle | |

|---|---|

Local service district / designated place | |

Welcome sign referencing the giant squid specimen of 1878 and its recognition by Guinness World Records | |

| |

Location within Newfoundland  Glovers Harbour Location within Canada | |

| Coordinates: 49°27′13″N 55°28′55″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Electoral district | Coast of Bays–Central–Notre Dame (federal)[1] Exploits (provincial)[2][3] |

| Census division | 8 (subdivision E)[4] |

| Settled | late 1800s[5] (≤1878) |

| Founded by | Joseph Martin[5] |

| Named for | John Hawley Glover[5] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.42 km2 (3.25 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–20 m (0–66 ft) |

| Population (2021 census)[6] | |

| • Total | 55 |

| • Density | 6.5/km2 (17/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−03:30 (NST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−02:30 (NDT) |

| Postal code | A0H 1E0[7] |

| Area code | 709 (COC: 483)[7] |

| NTS map no. | 002E06[8] |

| GNBC code | AAIAE[8] |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

Settled sometime in the second half of the 19th century, Glovers Harbour has remained primarily a fishing village throughout its history. It is best known for the giant squid that was captured on its shores in 1878, which was subsequently recognised as a world record by Guinness. Glovers Harbour brands itself as the "home of the giant squid" and has a small heritage centre and "life-sized" sculpture dedicated to the animal, these being its main tourist attractions.[20]

History

The settlement was named after John Hawley Glover, who served as the Governor of Newfoundland in 1876–1881 and again in 1883–1885.[5][21]

![Joseph Martin (1838–1920), founder of Glovers Harbour,[22] pictured around 1880[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/10/Joseph_Martin_%28Glovers_Harbour%29.jpg/180px-Joseph_Martin_%28Glovers_Harbour%29.jpg)

Early years

According to local tradition, Glovers Harbour was founded by Joseph Martin, originally of Harbour Grace,[lower-alpha 2] who settled there sometime in the late 1800s.[5][21] Martin's daughter married the son of George Marsh, the first permanent settler of nearby Winter House Cove, and the two families remained the main inhabitants of Glovers Harbour until the arrival of Alex Boone, previously of Cottrell's Cove.[5]

Glovers Harbour first appeared in the Canadian national census of 1901, under the name Glover Harbor, when its population was recorded as 67, though this included the inhabitants of Leading Tickles and Lock's Harbour (later Lockesport(e) or Lockport[25]).[5][26] In the 1911 census, it was listed as Glover's Harbor, with a population of 28 Newfoundland-born residents, predominantly followers of the Church of England, though one Methodist was also recorded.[5][10] The population fell to a low of 11 at the time of the 1921 census[11][27] but rebounded to 29 in 1935[12][28] and 38 in 1945.[13][29]

Resettlement period

From its founding, small-scale inshore cod fishing was the mainstay of the local economy, supplemented by seasonal work such as logging as well as livestock and vegetable farming.[5][21] By the middle of the 20th century, however, a lack of transport infrastructure left the isolated residents of Glovers Harbour with few other job opportunities.[5] The 1962 construction of a road connecting Glovers Harbour to Route 350 was transformative, as it opened access to the commercially important town of Botwood and to the nearby fish markets of Leading Tickles and Point Leamington.[5][21] Movement of people from more isolated nearby communities to Glovers Harbour soon followed, largely motivated by a Newfoundland-wide government resettlement program, though some early moves occurred without government assistance.[5][21]

Despite being larger at the time, the neighbouring communities of Lockesporte and Winter House Cove (both located in Seal Bay) were never connected to the road network owing to the difficulty of the surrounding terrain, and this contributed to their rapid decline and eventual abandonment by the close of the 1960s.[25][30][31] As recorded in the 1971 census, eight families totalling 39 people (predominantly with the surname Haggett) had moved to Glovers Harbour from Lockesporte alone.[5][lower-alpha 3] At least four families (Burton, followed by Goudie, Haggett, and Rowsell) had similarly resettled from Winter House Cove by this point.[5] As a result, the population of Glovers Harbour swelled almost threefold between 1966 and 1971, from 52 to 145.[5][32]

![Salvation Army Sunday school in Lock's Harbour, c. 1945. Numbering around two dozen children, it included pupils from Glovers Harbour and Winter House Cove.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Salvation_Army_Sunday_School%2C_Lock%27s_Harbour.jpg/260px-Salvation_Army_Sunday_School%2C_Lock%27s_Harbour.jpg)

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| * Included inhabitants of Leading Tickles and Lock's Harbour.[5] § Population initially reported as 71[41] but later revised to 78.[40][42][lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The concomitant demographic changes turned Glovers Harbour into "a predominantly Salvation Army community".[5][21] The village's first Salvation Army citadel—which also served Lockesporte, Ward's Point, and Winter House Cove, and doubled up as a school—was erected on land belonging to Electra Martin.[5] This was followed by a second citadel, originally constructed near Flag Pond around 1942, that was later moved close to Glovers Harbour Road.[5]

During resettlement, Winter House Cove's Anglican church—a school chapel first recorded in the 1901 census—was floated (transported over water) to Glovers Harbour, where it found use as a school until the late 1960s.[5] Both this school and another one that had been built in Glovers Harbour by the 1960s were later closed; thereafter, students attended elementary school in Leading Tickles and high school in Point Leamington, which were reached by school bus.[5] The Anglican church was subsequently renovated and held fortnightly services presided over by a visiting minister from Botwood.[5]

From its peak following resettlement, the population of Glovers Harbour dropped to 136 by 1981[5][34] and continued to gradually contract over the next three decades.[35][37][38][39][40]

Contemporary history

Over time, the fishery in Glovers Harbour has diversified to encompass lobster, capelin, squid, and queen crab (also known as snow crab).[21] In 1997, a proposal was submitted to recognise the coastal area around Leading Tickles and Glovers Harbour as a Marine Protected Area (MPA).[44] On 8 June 2001, the area officially came under consideration to become an MPA when it was identified as an Area of Interest by the minister for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO).[44]

Geography

Glovers Harbour is in Newfoundland within Subdivision E of Division No. 8.[45]

A promontory on the southern shore of Glovers Harbour is known as Glovers Point.[19][46] Glovers Harbour also gives its name to the Glovers Harbour Formation, a sequence of volcanic rocks of the Wild Bight Group that lie to its west.[47][48] Other geographical points of interest include an unmarked trail called Rowsell's Trail.[21]

Glovers Harbour is surrounded "by rolling green hillsides and glacial lakes, making it incredibly picturesque for those who have never visited Newfoundland before".[20]

Thimble Tickle

Glovers Harbour was formerly known as Thimble Tickle(s).[18][20][25][22] In Newfoundland English, a tickle is a narrow strait (see List of tickles). The name Thimble Tickle (and variants thereof) has been applied to a number of related geographical features. The Gazetteer of Canada of 1968 lists Thimble Tickles (a series of channels), Thimble Head, and Thimble Tickle Head (both headlands) as features in the same general area.[19] Other associated geographical names include Cumlins Cove and Cumlins Head, both listed by the Gazetteer as features of Thimble Tickle(s).[19] According to the Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, Thimble Tickles is a "scattered group of islands" in the vicinity of Glovers Harbour.[5] It has also been described as "a passage between several islands south of Leading Tickles and a few kilometres north of Glovers Harbour".[23]

Thimble Tickle Prospect, also known as the Lockport Mine (after Lockport), was a copper and sulfur mine located "over the hill" and just west of Glovers Harbour.[48][25] It operated intermittently in the 1880s and 1890s; the shafts were sealed around 1999.[25]

Demographics

As a designated place in the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Glovers Harbour recorded a population of 55 living in 28 of its 39 total private dwellings, a change of -40.2% from its 2016 population of 92. With a land area of 8.42 km2 (3.25 sq mi), it had a population density of 6.5/km2 (16.9/sq mi) in 2021.[6]

The 2016 census recorded a median value of dwellings of CA$100,161 (equivalent to US$75,570 in 2021).[40] The median total household income was CA$61,824 (equivalent to US$46,646 in 2021).[40]

Governance

Glovers Harbour is a local service district (LSD)[49] that is governed by a committee responsible for the provision of certain services to the community.[50] The chair of the LSD committee is Ida Haggett.[49]

Giant squid

Thimble Tickle specimen

Glovers Harbour is best known for its association with the giant squid (Architeuthis dux).[21] On 2 November 1878, a live animal reportedly 55 ft (16.8 m) long, which came to be known as the "Thimble Tickle specimen", was found aground offshore.[51][52][53][54][55] It was secured to a tree with a grapnel and rope and died as the tide receded. No parts of the animal were saved and no photographs or exact measurements exist as the specimen was cut up for dog food soon after its discovery; practically all that is known of it comes from a second-hand account by Reverend Moses Harvey in a letter to the Boston Traveller dated 30 January 1879, which was reproduced in the works of Yale zoologist Addison Emery Verrill the following year:

On the 2d day of November last, Stephen Sherring, a fisherman residing in Thimble Tickle, not far from the locality where the other devil-fish [the "Three Arms specimen"], was cast ashore, was out in a boat with two other men; not far from the shore they observed some bulky object, and, supposing it might be part of a wreck, they rowed toward it, and, to their horror, found themselves close to a huge fish, having large glassy eyes, which was making desperate efforts to escape, and churning the water into foam by the motion of its immense arms and tail. It was aground and the tide was ebbing. From the funnel at the back of its head it was ejecting large volumes of water, this being its method of moving backward, the force of the stream, by the reaction of the surrounding medium, driving it in the required direction. At times the water from the siphon was black as ink.

Finding the monster partially disabled, the fishermen plucked up courage and ventured near enough to throw the grapnel of their boat, the sharp flukes of which, having barbed points, sunk into the soft body. To the grapnel they had attached a stout rope which they had carried ashore and tied to a tree, so as to prevent the fish from going out with the tide. It was a happy thought, for the devil fish found himself effectually moored to the shore. His struggles were terrific as he flung his ten arms about in dying agony. The fishermen took care to keep a respectful distance from the long tentacles, which ever and anon darted out like great tongues from the central mass. At length it became exhausted, and as the water receded it expired.

The fishermen, alas! knowing no better, proceeded to convert it into dog's meat. It was a splendid specimen—the largest yet taken—the body measuring 20 feet [6.1 m] from the beak to the extremity of the tail. It was thus exactly double the size of the New York specimen [better known as the "Catalina specimen"], and five feet [1.5 m] longer than the one taken by [fisherman William] Budgell [the "Three Arms specimen"]. The circumference of the body is not stated, but one of the arms measured 35 feet [10.7 m]. This must have been a tentacle.[51][52]

![George Marsh (1825–1911) may have been involved in the capture of the giant squid.[25] He and his wife Louisa were the first permanent settlers of Winter House Cove c. 1858.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/George_Marsh_%28Winter_House_Cove%29.jpg/180px-George_Marsh_%28Winter_House_Cove%29.jpg)

Though the original account mentions only Stephen Sherring and two other (unnamed) fishermen,[51][52] later sources identify Glovers Harbour's founder, Joseph Martin, as one of the fishermen involved in the squid's capture.[25][22][23][56] George Marsh and Henry Rowsell—the founders of Winter House Cove and Lock's Harbour (Lockesporte), respectively—have also been suggested as participants.[25] The fishermen may have learned of Moses Harvey's interest in the giant squid when the latter visited Notre Dame Bay only a couple of months earlier, in August 1878, as part of a geological survey.[22] A CBC News report broadcast in 2004 features Maurice Martin, great-great-grandson of Joseph Martin, recounting the story of the squid's capture as told to him by his grandfather.[17]

The "Thimble Tickle specimen" has long[lower-alpha 6] been recognised by Guinness World Records and its prior incarnations as the largest giant squid ever recorded.[58][64][65][66] However, the reported measurements—particularly the length of the "body [..] from the beak to the extremity of the tail" (i.e. mantle plus head) at 20 ft (6.1 m), but also the total length of 55 ft (16.8 m)—greatly exceed all modern, scientifically verified records, which encompass several hundred specimens.[60][61][62][63] Such lengths are now generally regarded as exaggerations and often attributed to artificial lengthening of the two long feeding tentacles (analogous to stretching elastic bands) or to inadequate measurement methods such as pacing.[60][61][67] Over time, various other superlative measurements have been attributed to the specimen, including a mass of 2 tonnes (2.2 short tons; 4,400 lb)[22][68] or exactly 4,480 lb (2,030 kg);[57] an eye diameter of 40 cm (16 in),[22][68] 18 in (46 cm),[69] or 9 in (23 cm);[57][58] and suckers 4 in (10 cm) across.[69] Additionally, a number of extreme mass estimates have been published for the specimen.[lower-alpha 7]

Giant Squid Interpretation Site

Today, a small heritage centre and a "life-sized", 55-foot giant squid sculpture—collectively known as the Giant Squid Interpretation Site—stand near the site of the specimen's capture[17][74] and are the community's main tourist attractions.[21][75][76] The sculpture was completed in 2001[23] following a CA$100,000 government contribution (equivalent to US$64,568 in 2021); ten thousand visitors were expected in the first year.[17][16] It weighs four tonnes and was constructed from a combination of steel, wire mesh, and concrete.[17][16][77] The sculpture was designed by fine arts teacher Don Foulds of Saskatoon[lower-alpha 8] and built by him and his students, with help from Jason Hussey, Niel McLellan, and Edward O'Neill.[17][16] It has been described as "a beautiful reproduction" by Spanish giant squid experts.[78] The sculpture featured on a Canada Post stamp issued in 2011 as part of the "Roadside Attractions" series, with a print run of 1,045,000.[16][79]

The heritage centre opened in 2009 and includes a small museum, a gift shop, and a picnic area.[74][75] The museum details the capture of the Thimble Tickle specimen—including among its collections the "official records of the encounter"[20] and a "life-sized" replica of the squid's eyeball[23]—but also the history of the local area and particularly its fishing heritage.[20]

See also

- List of communities in Newfoundland and Labrador

- List of designated places in Newfoundland and Labrador

- List of local service districts in Newfoundland and Labrador

- Museo del Calamar Gigante – giant squid museum in Luarca, Spain

- Noto, Ishikawa – Japanese town with large squid statue as tourist attraction

Notes

- Sometimes written with an apostrophe, especially historically,[10][11][12][13][14][15] though also more recently,[16] including on the community's welcome sign.

- Lovell's Province of Newfoundland Directory for 1871 lists[24] two people by this name residing in Harbour Grace—a carpenter and a labourer.[5]

- The remainder resettled to Leading Tickles, Point Leamington, and Deer Lake.[30]

- Per Statistics Canada, Glovers Harbour "underwent a boundary change since the 2011 Census that resulted in an adjustment to the 2011 population and/or dwelling counts for the area".[43]

- The count from the 1901 census has been omitted as it included the inhabitants of Leading Tickles and Lock's Harbour.[5]

- An early example comes from the 1968 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records, which gives an erroneous provenance (corrected by the 1971 edition[57]):

The heaviest of all invertebrate animals is the Atlantic giant squid (Architeuthis princeps). The largest specimen ever recorded was one measuring 55 feet [16.8 m] overall, captured on November 2, 1878, after it had run aground on Thimble Tickle, one of the Thimble Islands off the coast of Connecticut [sic]. Its eyes were 9 inches [23 cm] in diameter.[58]

For comparison, the first US edition, titled The Guinness Book of Superlatives and published in 1956, gives more modest maximum dimensions:The giant squid (Architeuthis) found on the Newfoundland Banks may have a body length of 8 feet [2.4 m] and measure up to 40 feet [12 m] overall.[59]

These measurements closely agree with current understanding of the giant squid's maximum size.[60][61][62][63] - Wildly excessive mass estimates for the "Thimble Tickle specimen" have included:[54][64] 29.25 or 30 short tons (26.5 or 27.2 tonnes; 58,500 or 60,000 pounds);[70] near 24 tonnes (26 short tons; 53,000 lb);[71] less than 8 tonnes (8.8 short tons; 18,000 lb);[72] and 2.8 or "more realistic[ally]" 2 tonnes (3.1 or 2.2 short tons; 6,200 or 4,400 lb).[64][73]

- Foulds was chosen because of his experience building large-scale community monuments in Saskatchewan, including "a giant turtle, a moose and a woolly mammoth".[17][77]

References

- Coast of Bays—Central—Notre Dame. Elections Canada.

- House of Assembly Act, RSNL 1990, c H-10. Queen's Printer, St. John's.

- Elections Newfoundland & Labrador (2020). 2019 Provincial General Election Report. St. John's. 330 pp.

- Statistics Canada (2007). Standard Geographical Classification (SGC), 2006. Volume I. The Classification. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 12-571-XIE. Ottawa. 635 pp. ISBN 0-662-43691-1. [See also archived page for Division No. 8, Subd. E.]

- Smallwood, J.R., R.D.W. Pitt, C. Horan & B.G. Riggs (eds.) (1984). Glovers Harbour. [pp. 539–540] In: Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador. Volume 2: Fac–Hoy. Newfoundland Book Publishers, St. John's. xiii + 1104 pp. ISBN 978-0-920508-16-9.

- Statistics Canada (2022). Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population: Glovers Harbour, Designated place (DPL), Newfoundland and Labrador. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released 9 February 2022.

- Newfoundland and Labrador Directory of Local Service Districts. Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism, St. John's. 5 pp.

- Glovers Harbour. Natural Resources Canada.

- Consolidated Newfoundland Regulation 1028/96. Queen's Printer, St. John's.

- Colonial Secretary's Office (1914). Glover's Harbor. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/56668 206], 208, 210] In: Census of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1911. Table I. Population, sex, condition, denomination, profession, &c. J.W. Withers, St. Jonh's. xxxi + 505 pp. OCLC 21658161

- Colonial Secretary's Office (1923). Glover's Harbor. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/49155 206], 208, 210] In: Census of Newfoundland and Labrador 1921. Table I. Population, sex, condition, denomination, profession, etc. St. John's. xxiii + 512 pp. OCLC 797071136

- Department of Public Health and Welfare (1937). Glover's Harbour. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/51209 42], 190, 452, 608, 868] In: Tenth Census of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1935. Volume I. Population by districts and settlements. The Evening Telegram, St. John's. 961 + xxix pp. OCLC 8351268

- Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1949). Glover's Harbour. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/121911 3], 25, 54, 71, 94, 245] In: Eleventh Census of Newfoundland and Labrador 1945. Volume I. Population. Ottawa. xvi + 252 pp. OCLC 21641833

- Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1957). Census of Canada, 1956: population of unincorporated villages and settlements. Catalogue no. 6009-582. Ottawa. 64 pp.

- Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1968). Census of Canada – 1966. Population: unincorporated places. Catalogue no. 6009-573. Ottawa. 194 pp.

- The Giant Squid - Glover's Harbour. Postage Stamp Guide.

- Harvey, K. (reporter) (2004). Sizable squid in Glovers Harbour, N.L.. [video] CBC Here & Now, 23 January 2004.

- Dave Marsh interview, March 29, 1988. [audio recording] Digital Archives Initiative, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Canadian Permanent Committee on Geographical Names (1968). Gazetteer of Canada: Newfoundland and Labrador. Energy, Mines and Resources Canada, Ottawa. xiii + 252 pp. OCLC 395303369

- Machado, K. (2021). Thimble Tickle: Home Of The Giant Squid (And A Quaint Fishing Village). TheTravel, 27 August 2021.

- Socio-economic overview of Leading Tickles Area of Interest (AOI), Newfoundland: executive summary. Department of Fisheries and Oceans, May 2004. 16 pp.

- The Giant Squid of Thimble Tickle. [information plaque] Giant Squid Interpretation Site, Glovers Harbour.

- Hynes, B. (2012). The kraken's spawn. [pp. 1–27] In: Here Be Dragons: Strange Creatures of Newfoundland and Labrador. Breakwater Books, St. John's. xiii + 210 + [4] pp. ISBN 978-1-55081-384-5.

- Lovell, J. (1871). Harbor Grace. [pp. 259–262] In: Lovell's Province of Newfoundland Directory for 1871. John Lovell, Montreal. 380 pp. OCLC 1019499731

- Marsh, B. (2016). Resettlement in our backyard. Anglo Newfoundland Development Company, 25 July 2016.

- Colonial Secretary's Office (1903). Glover Harbor. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/158503 176], 178, 180] In: Census of Newfoundland and Labrador 1901. Table I. Population, sex, condition, denominations, professions, &c. J.W. Withers, St. Jonh's. xxx + 457 pp. OCLC 456605290

- Newfoundland 1921 Census: Glovers Harbour, Twillingate District. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Newfoundland's 1935 Provincial Census, District of Twillingate: Community of Glovers Harbour. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Newfoundland's 1945 Provincial Census, Green Bay District: Community of Glover's Harbour. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Smallwood, J.R., C.F. Poole & R.H. Cuff (eds.) (1991). Lockesporte. [p. 355] In: Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador. Volume 3: Hub–M. Harry Cuff Publications, St. John's. xvii + 687 pp. ISBN 978-0-9693422-2-9.

- Poole, C.F. & R.H. Cuff (eds.) (1994). Winter House Cove, Seal Bay. [p. 590] In: Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador. Volume 5: S–Z. Harry Cuff Publications, St. John's. xv + 706 pp. ISBN 978-0-9693422-5-0.

- Statistics Canada (1973). Special bulletin: 1971 Census of Canada. Population: unincorporated settlements. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 92-771. Ottawa. 215 pp.

- Statistics Canada (1978). 1976 Census of Canada. Supplementary bulletins: geographic and demographic. Population of unincorporated places – Canada. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 92-830. Ottawa. vi + 128 pp.

- Statistics Canada (1983). 1981 Census of Canada. Place name reference list: Atlantic provinces. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 94-902. Ottawa. xii + [199] pp.

- Statistics Canada (1987). Population and dwelling counts – Canada: unincorporated places. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 92-105. Ottawa. xxxv + 360 pp.

- Statistics Canada (1993). Unincorporated places: population and dwelling counts. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 93-306. Ottawa. 213 pp.

- Population of Communities by Consolidated Census Subdivision (CCS): Newfoundland and Labrador, 1991 and 1996 Census. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Population of Communities by Census Consolidated Subdivision (CCS): Newfoundland and Labrador, 2001 Census. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Population of Communities by Census Consolidated Subdivision (CCS): Newfoundland and Labrador, 2006 Census. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Statistics Canada (2017). Census Profile, 2016 Census: Glovers Harbour, Designated place, Newfoundland and Labrador and Newfoundland and Labrador. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released 29 November 2017.

- 2011 Census Population, Census Consolidated Subdivisions (CCS) by Community: Newfoundland and Labrador. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- 2016 Census Population, by 2011 Census Consolidated Subdivision (CCS) by Community: Newfoundland and Labrador. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. Modified 7 February 2018.

- Power, A.S. & D. Mercer (2002). The role of fishers knowledge in implementing ocean act initiatives in Newfoundland and Labrador. [pp. 20–24] In: N. Haggan, C. Brignall & L. Wood (eds.) Putting fishers' knowledge to work: conference proceedings August 27–30, 2001. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 11(1): 1–504.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions, census subdivisions (municipalities) and designated places, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Newfoundland and Labrador)". Statistics Canada. February 7, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- Glovers Point. Natural Resources Canada.

- MacLachlan, K., B.H. O'Brien & G.R Dunning (2001). Redefinition of the Wild Bight Group, Newfoundland: implications for models of island-arc evolution in the Exploits Subzone. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38(6): 889–907. doi:10.1139/e01-006

- Lockport Mine – Copper–Zinc. The Matty Mitchell Prospectors Resource Room, October 2010.

- "Directory of Local Service Districts" (PDF). Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. October 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Local Service Districts – Frequently Asked Questions". Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- Verrill, A.E. (1880). The cephalopods of the north-eastern coast of America. Part I.—The gigantic squids (Architeuthis) and their allies; with observations on similar large species from foreign localities. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 5(1)[Dec. 1879 – Mar. 1880]: 177–257. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.35965

- Verrill, A.E. (1880). Synopsis of the Cephalopoda of the north-eastern coast of America. The American Journal of Science (ser. 3)19(112)[Apr.]: 284–295.

- Hatton, J. & M. Harvey (1883). Newfoundland: The Oldest British Colony. Its history, its present condition, and its prospects in the future. Chapman & Hall, London. xx + 489 pp.

- Ellis, R. (1998). The Search for the Giant Squid. Lyons Press, New York. ix + 322 pp. ISBN 1-55821-689-8.

- Sweeney, M.J. & C.F.E. Roper (2001). Records of Architeuthis Specimens from Published Reports. [Last updated 4 May 2001.] National Museum of Natural History. 132 pp. [unpaginated] [Archived from the original on 2 October 2011.]

- A Collection of Newfoundland Wills (M): Abraham Martin. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- McWhirter, N. & R. McWhirter (1971). Mollusks: Largest. [p. 88] In: Guinness Book of World Records. Sterling Publishing Company, New York. 608 pp. ISBN 0-8069-0004-0.

- McWhirter, N. & R. McWhirter (1968). Mollusks: Largest. [p. 59] In: Guinness Book of World Records. Sterling Publishing Company, New York. 464 pp. OCLC 2541308

- McWhirter, N. & P. Page (1956). Mollusks: Largest. [p. 101] In: The Guinness Book of Superlatives. Superlatives Inc., New York. 224 pp. OCLC 972777

- O'Shea, S. & K. Bolstad (2008). Giant squid and colossal squid fact sheet. The Octopus News Magazine Online, 6 April 2008.

- Roper, C.F.E. & E.K. Shea (2013). Unanswered questions about the giant squid Architeuthis (Architeuthidae) illustrate our incomplete knowledge of coleoid cephalopods. American Malacological Bulletin 31(1): 109–122. doi:10.4003/006.031.0104

- Yukhov, V.L. (2014). Гигантские кальмары рода Architeuthis в Южном океане / Giant calmaries Аrchiteuthis in the Southern ocean. [Gigantskiye kalmary roda Architeuthis v Yuzhnom okeane.] Ukrainian Antarctic Journal no. 13: 242–253. (in Russian)

- McClain, C.R., M.A. Balk, M.C. Benfield, T.A. Branch, C. Chen, J. Cosgrove, A.D.M. Dove, L.C. Gaskins, R.R. Helm, F.G. Hochberg, F.B. Lee, A. Marshall, S.E. McMurray, C. Schanche, S.N. Stone & A.D. Thaler (2015). Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ 3: e715. doi:10.7717/peerj.715

- Wood, G.L. (1982). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. [third edition] Guinness Superlatives, London. 252 pp. ISBN 0-85112-235-3.

- Carwardine, M. (1995). The Guinness Book of Animal Records. Guinness Publishing, Enfield. 256 pp. ISBN 0-85112-658-8.

- Glenday, C. (ed.) (2014). Mostly molluscs. [pp. 62–63] In: Guinness World Records 2015. Guinness World Records. 255 pp. ISBN 1-908843-70-5.

- Dery, M. (2013). The Kraken wakes: what Architeuthis is trying to tell us. Boing Boing, 28 January 2013.

- Ganeri, A. (1990). The Usborne Book of Ocean Facts. Usborne Publishing, London. 48 pp. ISBN 978-0-7460-0621-4.

- The undeniable Kraken. American Oceanography [1968]: 1, 7.

- MacGinitie, G.E. & N. MacGinitie (1949). Natural History of Marine Animals. McGraw-Hill, New York. xii + 473 pp. OCLC 489962159

- Heuvelmans, B. (1958). Dans le sillage des monstres marins: le kraken et le poulpe colossal. Plon, Paris. OCLC 16321559 (in French)

- MacGinitie, G.E. & N. MacGinitie (1968). Natural History of Marine Animals. [second edition] McGraw-Hill, New York. xii + 523 pp. OCLC 859568740

- Akimushkin, I.I. (1963). Головоногие моллюски морей СССР. [Golovonogie Mollyuski Morei SSSR.] Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R., Moscow. 233 + [3] pp. OCLC 13632765 (in Russian) [English translation from Russian by A. Mercado: Akimushkin, I.I. (1965). Cephalopods of the Seas of the U.S.S.R. Israel Program for Scientific Translations, Jerusalem. viii + 223 pp. OCLC 557215373]

- Hickey, S. (2009). Super squid: Museum set to open next month. Advertiser (Grand Falls), 25 May 2009.

- 2018 Traveller's Guide: Lost and Found. Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism, St. John's. 460 pp.

- McConvey, J.R. (2015). Close Encounters with a Big Squid. Hakai Magazine, 11 May 2015.

- Life-Size Statue of Monster Squid. RoadsideAmerica.com.

- Guerra, Á., Á.F. González, F. Rocha, J. Gracia & L. Laria (2006). Enigmas de la Ciencia: El Calamar Gigante. CEPESMA, Vigo. 313 pp. ISBN 978-84-609-9999-7. (in Spanish)

- Hickey, S. (2010). Canada Post celebrates the giant squid. Advertiser (Grand Falls), 17 June 2010. [Reprinted in: The Packet (Clarenville), 24 June 2010, p. 32 and The Beacon (Gander), 30 June 2010, p. A8.]

- Holder, C.F. (1885). Marvels of Animal Life. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. x + 240 pp. OCLC 29790638

Further reading

- Anon. (2000). Salute to Newfoundland communities: Glovers Harbour. The Newfoundland Herald vol. 55, no. 8.

- Carberry, N. (2001). Giant squid makes second landing in Glovers Harbour. Advertiser (Grand Falls) vol. 65, no. 63.

- Glover's Harbour: New Cemetery. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

External links

- History of Glovers Harbour on YouTube

- Drone footage of Glovers Harbour on YouTube

- "Doorstep of Heaven" – musical tribute to Glovers Harbour on YouTube

- Giant Squid Interpretation Site – Adventure Central Newfoundland

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии

![Artist's impression of the Thimble Tickle specimen, from Charles Holder's Marvels of Animal Life (1885)[80]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d7/Thimble_Tickle_giant_squid.jpg/298px-Thimble_Tickle_giant_squid.jpg)