geo.wikisort.org - Mountains

Hampstead Heath (locally known simply as the Heath) is an ancient heath in London, spanning 320 hectares (790 acres).[1] This grassy public space sits astride a sandy ridge, one of the highest points in London, running from Hampstead to Highgate, which rests on a band of London Clay.[2] The heath is rambling and hilly, embracing ponds, recent and ancient woodlands, a lido, playgrounds, and a training track, and it adjoins the former stately home of Kenwood House and its estate. The south-east part of the heath is Parliament Hill, from which the view over London is protected by law.

| Hampstead Heath | |

|---|---|

Corporation of London sign on the south-west edge of the heath. | |

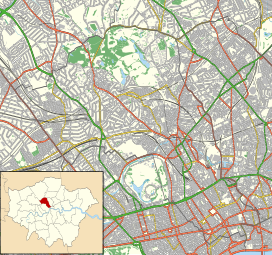

Location within central London | |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | London, England |

| Coordinates | 51°33′37″N 0°9′39″W |

| Area | 790 acres (320 ha) |

| Operated by | Corporation of London |

| Status | Open year round |

| Website | City of London: Hampstead Heath |

Running along its eastern perimeter is a chain of ponds – including three open-air public swimming pools – which were originally reservoirs for drinking water from the River Fleet. The heath is a Site of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation,[3] and part of Kenwood is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Lakeside concerts are held there in summer. The heath is managed by the City of London Corporation, and lies mostly within the London Borough of Camden with the adjoining Hampstead Heath Extension and Golders Hill Park in the London Borough of Barnet.

History

The heath first entered the history books in 986 when Ethelred the Unready granted one of his servants five hides of land at "Hemstede". This same land is later recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as held by the monastery of St. Peter's at Westminster Abbey, and by then is known as the "Manor of Hampstead".[4] Westminster held the land until 1133 when control of part of the manor was released to one Richard de Balta; then during Henry II's reign the whole of the manor became privately owned by Alexander de Barentyn, the King's butler. Manorial rights to the land remained in private hands until the 1940s when they lapsed under Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon Wilson,[citation needed] though the estate itself was passed on to Shane Gough, 5th Viscount Gough.[4]

Over time, plots of land in the manor were sold off for building, particularly in the early 19th century, though the heath remained mainly common land. The main part of the heath was acquired for the people by the Metropolitan Board of Works.[5] Parliament Hill was purchased for the public for £300,000 and added to the park in 1888. Golders Hill was added in 1898 and Kenwood House and grounds were added in 1928.[6]

From 1808 to 1814 Hampstead Heath hosted a station in the shutter telegraph chain which connected the Admiralty in London to its naval ships in the port of Great Yarmouth.

The City of London Corporation has managed the heath since 1989.[7] Before that it was managed by the GLC and before that by the London County Council (LCC).

In 2021, Quiet Parks International—a non-profit organisation whose aim is to identify locations around the world that remain free from human-made noise for at least brief periods—gave Hampstead Heath "Urban Quiet Park" status.[8]

Geography

The heath sits astride a sandy ridge that rests on a band of London clay. It runs from east to west, its highest point being 134 metres (440 ft).[9][10] As the sand was easily penetrated by rainwater which was then held by the clay, a landscape of swampy hollows, springs and man-made excavations was created.[2] Hampstead Heath contains the largest single area of common land in Greater London, with 144.93 hectares (358.1 acres) of protected commons.[11]

Public transport near the heath includes London Overground railway stations Hampstead Heath and Gospel Oak and London Underground stations at Hampstead and Belsize Park to the south, Golders Green to the north-west, and Highgate and Archway to the east. Buses serve several roads around the heath.

Areas of the heath

The heath's 320 hectares (790 acres) include a number of distinct areas.

Whitestone, Highgate and Hampstead Ponds

Hampstead Heath has over 25 ponds; most of these are in two distinct areas: the Highgate Ponds and the Hampstead Ponds.

Whitestone Pond

Whitestone Pond is a roughly triangular pond, centrally located on the heath's south side and north-northwest of Queen Mary's House (formerly a care home and before that a maternity hospital), across busy Heath Street (A502). Originally a small dew pond called the Horse Pond, it was renamed after a waypoint stone and is artificially fed.[12] It has an exposed location, closely surrounded by roads, which limits its recreational use. It is the heath's best known body of water, and many people's introduction to Hampstead Heath's ponds.

Highgate Ponds

Highgate Ponds are a series of eight former reservoirs, on the heath's east (Highgate) side, and were originally dug in the 17th and 18th centuries.[13] They include two single-sex swimming pools (the men's and ladies' bathing ponds), a model boating pond, and two ponds which serve as wildlife reserves: the Stock Pond and the Bird Sanctuary Pond. Fishing is allowed in some of the ponds, although this is threatened by proposals to modify the dams.

The ponds are the result of the 1777 damming of Hampstead Brook (one of the Fleet River's sources), by the Hampstead Water Company, which was formed in 1692 to meet London's growing water demands.[2]

"Boudicca's Mound", near the present men's bathing pond, is a tumulus where, according to local legend, Queen Boudicca (Boadicea) was buried after she and 10,000 Iceni warriors were defeated at Battle Bridge.[14] However, historical drawings and paintings of the area show no mound other than a 17th-century windmill.

Hampstead Ponds

The Hampstead Ponds are three ponds in the heath's south-west corner, towards South End Green. Hampstead Pond #3 is the mixed bathing pond, where both sexes may swim.

Pond maintenance

In 2004 the City of London Corporation, rejected a proposal by the Hampstead Heath Winter Swimming Club to allow "early-morning, self-regulated swimming in the mixed sex pond on Hampstead Heath"; the Corporation argued that it risked legal action by the Health and Safety Executive if it allowed such swimming, since the Executive had refused to give assurances to the Corporation that it would not be prosecuted under the Health and Safety at Work Act. The swimmers successfully challenged this in the High Court, which in 2005 ruled that members of the swimming club had the right to swim at their own risk, and that the Corporation would not be liable under the Act for injuries as a result.[15][16]

In January 2011 the City of London announced a scheme which it said would improve the safety of the dams, to guard against damage that might result from a very large, but rare storm hitting London. The proposed engineering modifications of the dams were aimed at ensuring that three dams complied with the 1975 Reservoir Act. With the passage of the 2010 Flood and Water Management Act the City of London was advised that all the dams on the heath would need to comply with the reservoir safety regulations. The proposed works in 2011 included recommendations to improve the water quality of the lake, which had suffered from algae blooms. The proposals for the pond dams were extensively modified in 2012–2014. The proposals were challenged by a consortium of groups and societies collectively called "Dam Nonsense". However, with the dam project being now completed, many locals have begun to accept the changes as wildlife begins to soften the border between the artificial and the natural in this area.

Caen Wood Towers

To the north east of the heath is a derelict site within the conservation area comprising the grounds and mansion of the former Caen Wood Towers (renamed Athlone House in 1972). This historic building, currently in disrepair, was built in 1872 for Edward Brooke, aniline dye manufacturer (architect, Edward Salomons). In 1942 the building was taken for war service by the Royal Air Force and was used to house the RAF Intelligence School, although the 'official' line was that it was a convalescence hospital. The Operational Record (Form 540) of RAF Station Highgate (currently in the National Archives, Kew) was declassified in the late 1990s and shows the true role of this building in wartime service. The building sustained 2 near misses from V-1 flying bombs in late 1944, causing damage and injuries to staff. The RAF Intelligence School remained in Caen Wood Towers until 1948, when the building was handed over to the Ministry of Health. It was then used as a hospital and finally a post-operative recovery lodge, before falling into disrepair in the 1980s. The NHS sold off this part of their estate in 2004 to a private businessman who is currently redeveloping much of the site; however the House and its gardens fall within the conservation area of Hampstead Heath.

Parliament Hill Fields

Parliament Hill Fields lies on the south and east of the heath; it officially became part of the heath in 1888. It contains various sporting facilities including an athletics track, tennis courts and Parliament Hill Lido.[17] Parliament Hill itself is considered by some to be the focal point of the heath,[18] with the highest part of it known to some as "Kite Hill" due to its popularity with kite flyers.[19] The hill is 98.1 metres (322 ft) high and is notable for its excellent views of the London skyline. The skyscrapers of Canary Wharf and the City of London can be seen, along with St Paul's Cathedral and other landmarks, all in one panorama, parts of which are protected views. The main staff yards for the management of the heath are located at Parliament Hill Fields.[7]

In the south-east of the heath, on the southern slopes of Parliament Hill, is the Gospel Oak Lido open air swimming pool, with a running track and fitness area to its north.

Kenwood

The area to the north of the heath is the Kenwood Estate and House – a total area of 50 hectares (120 acres) which is maintained by English Heritage. This became part of the heath when it was bequeathed to the nation by Lord Iveagh on his death in 1927, and opened to the public in 1928. The original house dates from the early 17th century. The orangery was added in about 1700.

Hampstead Heath Woods

One third of the Kenwood estate (Ken Wood and North Wood) is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest, designated by Natural England.[20][21]

The Vale of Health

The Vale of Health is a hamlet accessed by a lane from East Heath Road; it is surrounded entirely by the heath. In 1714, one Samuel Hatch, a harness maker, built a workshop and was granted some land. By 1720, he had a cottage at what was subsequently called Hatch's or Hatchett's Bottom. A new name, considered given in deliberate attempt to change the image of a developing location, the Vale of Health, was recorded in 1801.[22]

Extension

The Extension is an open space to the north-west of the main heath. It does not share the history of common and heathland of the rest of the heath. Instead it was created out of farmland, largely due to the efforts of Henrietta Barnett who went on to found Hampstead Garden Suburb. Its farmland origins can still be seen in the form of old field boundaries, hedgerows and trees.

Golders Hill Park

Golders Hill Park is a formal park adjoining the West Heath. It occupies the site of a large house that was bombed during World War II. It has an expanse of grass, with a formal flower garden, a duck pond and a separate water garden that leads to a separate area for deer, near a recently renovated small zoo. The zoo has donkeys, maras, ring-tailed lemurs, ring-tailed coatis, white-cheeked turacos and European eagle-owls, among other animals. There are also tennis courts, a butterfly house and a putting green.[23]

Unlike the rest of the heath, Golders Hill Park is fenced in, and is closed at night.

Site of Special Scientific Interest

Ken Wood and North Wood are a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest called Hampstead Heath Woods, designated by Natural England.[24]

Constabulary

The heath is policed by the Hampstead Heath Constabulary, part of the City of London Corporation. Its 12 constable act as parks police and they are:

called upon to enforce Byelaws, Common Law and Criminal Law, protect City of London property and provide a response to any incident that may disrupt the enjoyment of users of these sites.[25]

From their inauguration until 24 May 2018 some constables worked with general purpose police dogs, all licensed to NPCC/Home Office standards. They have been responsible for patrolling the Heath since 1992.[26]

Activities

The heath is home to a range of activities, including 16 different sports.[7] It is used by walkers, runners, swimmers and kite-flyers. Running events include the weekly parkrun[27] and the annual Race for Life in aid of Cancer Research UK. Until February 2007 Kenwood held a series of popular lakeside concerts.

The West Heath is regarded as one of the safest night-time gay cruising grounds in London.[28] George Michael revealed that he cruised on the heath,[29] an activity he then parodied on the Extras Christmas Special.[30]

Swimming takes place all year round in two of the three natural swimming ponds: the men's pond which opened in the 1890s, and the ladies' pond which opened in 1925. The mixed pond is only open from May to September, though it is the oldest, having been in use since the 1860s.[31]

Facilities include an athletics track, a pétanque pitch, a volleyball court and eight separate children's play areas, including an adventure playground.[7]

In popular culture

While living in London, Karl Marx and his family went to the heath regularly, as their favourite outing.[32]

John Atkinson Grimshaw, Victorian-era painter, painted an elaborate night-time scene of Hampstead Hill in oils. Hampstead Heath also provided the backdrop for the opening scene in Victorian writer Wilkie Collins' novel The Woman in White.[citation needed]

Bram Stoker's novel Dracula is partly set on Hampstead Heath, in scenes when the undead Lucy abducts children playing on the heath.[citation needed]

Hampstead Heath forms part of the location for G. K. Chesterton's fictional story "The Blue Cross" from The Innocence of Father Brown.[33] The Heath is mentioned in Ralph Vaughan Williams' Symphony no. 2 'A London Symphony' with the subtitle 'Hampstead Heath on an August Bank Holiday'.

The photos used for the cover of The Kinks' LP The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society were taken on the heath in August 1968. In some photographs, Kenwood House is visible in the background.[citation needed]

Notting Hill (1999) featured scenes shot at the heath, located primarily around Kenwood House, where Julia Roberts' character was filming a movie.[34]

In 2005, Giancarlo Neri's sculpture The Writer, a 9-metre-tall table and chair, was exhibited on Hampstead Heath.[35]

The film Scenes of a Sexual Nature (2006) was shot entirely on Hampstead Heath.[36]

Colin Wilson slept rough (in a sleeping bag) on Hampstead Heath to save money when he was working on his first novel, Ritual in the Dark.[37]

In John le Carré's novel Smiley's People, the heath is the murder scene of General Vladimir, a pivotal event that leads to the downfall of George Smiley's nemesis Karla.[citation needed]

Gallery

Panorama of London from Kenwood (after completion of the Gherkin in 2003 but before the building of the Heron Tower in 2009–10).

- Kenwood House

- The Vale of Health

- The Writer, temporary structure in 2005

- Arsenal F.C.'s Emirates Stadium viewed from Hampstead Heath

- View towards St Jude's church in Hampstead Garden Suburb from the Heath extension

See also

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Greater London

- Camden parks and open spaces

- Barnet parks and open spaces

- Nature reserves in Barnet

References

- David Bentley (12 February 2010). "City of London Hampstead Heath". City of London. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Hampstead: Hampstead Heath – British History Online". british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Hampstead Heath". Greenspace Information for Greater London. 2006. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "Hampstead: Manor and Other Estates – British History Online". british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Thompson, Hampstead, 130, 165, 195, 317-18, 329- 30; G.L.R.O., E/MW/H, old no. 27/15 (sales parts. 1875).

- The London Encyclopaedia, Ben Weinreb & Christopher Hibbert, 1983, ISBN 0-333-57688-8

- "Hampstead Heath". cityoflondon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Moshakis, Alex (16 January 2022). "Noises off: the battle to save our quiet places". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 January 2022.

- Bathurst 2012, pp. 27–31.

- "London Borough Tops". The Mountains of England and Wales. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- "Common Land and the Commons Act 2006". Defra. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Hampstead: Hampstead Heath – British History Online". british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "CIX.co.UK: Hampstead Heath Ponds". Archived from the original on 4 January 2009.

- Humphreys, Rob; Bamber, Judith (2003). The Rough Guide to London. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-093-0. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- "Hampstead Heath Winter Swimming Club & Anor v Corporation of London & Anor [2005] EWHC 713 (Admin) (26 April 2005)".

- "Hardy bathers win right to swim unsupervised". the Guardian. 27 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- "Camden Council: Contact Parliament Hill Fields". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- "BBC – Seven Wonders – Parliament Hill". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Hampstead Heath – Sightseeing, Areas & Squares". Archived from the original on 22 December 2007.

- "Map of Hampstead Heath Woods SSSI". Natural England. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- "Natural England, Hampstead Heath Woods SSSI citation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- "Hampstead: Vale of Health". www.british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Contact Golders Hill Park". camden.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: Hampstead Heath Woods". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Constabulary - Visitor information". City of London. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Hampstead Heath Constabulary Annual Report 2015–16". Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Hampstead Heath parkrun – Weekly Free 5 km Timed Run". Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Gay venue search: Pink UK". pinkuk.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Howard, Patrick (30 July 2006). "Personal Column: 'I go with gay strangers. We have our own code'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- O'Donovan, Gerard (28 December 2007). "Last night on television: Extras Christmas Special (BBC1) – Battleship Antarctica (Channel 4)". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 1 January 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Greater London Authority – Press Release". Archived from the original on 7 October 2008.

- Mehring, Franz (2003). Karl Marx: The Story of His Life. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-415-31333-9. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Chesterton, G. K. The Innocence of Father Brown. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- "UK: Royals out in force for wedding". BBC News. 9 July 1999. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Moggach, Deborah; Richard Jinman (23 June 2005). "Heath's literary tribute makes handy goalposts". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Braun, Liz. "Sexual Nature all talk". Jam! Showbiz. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Desert Island Discs Archive: 1976–1980

Bibliography

- Bathurst, David (2012). Walking the county high points of England. Chichester: Summersdale. ISBN 978-1-84-953239-6.

- Fisher Unwin, T. (1913). Hampstead Heath: Its Geology and Natural History. London: Hampstead Scientific Society.

- Hewlett, Janet (1997). Nature Conservation in Barnet. London Ecology Unit. ISBN 1-871045-27-4.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher (2010). The London Encyclopaedia. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1405049252.

External links

- The official Hampstead Heath pages on the City of London website

- Comprehensive and detailed website for Hampstead Heath

- History of Hampstead Heath

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии