geo.wikisort.org - Mountains

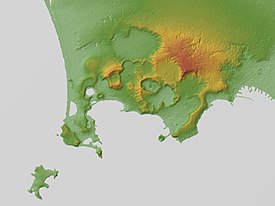

The Phlegraean Fields (Italian: Campi Flegrei [ˈkampi fleˈɡrɛi]; Neapolitan: Campe Flegree, from Ancient Greek φλέγω phlego 'to burn')[2][citation needed] is a large volcano situated to the west of Naples, Italy. It was declared a regional park in 2003. The area of the caldera consists of 24 craters and volcanic edifices; most of them lie under water. Hydrothermal activity can be observed at Lucrino, Agnano and the town of Pozzuoli. There are also effusive gaseous manifestations in the Solfatara crater, the mythological home of the Roman god of fire, Vulcan. This area is monitored by the Vesuvius Observatory.[3] It is considered a supervolcano.[4][5][6]

| Phlegraean Fields | |

|---|---|

Phlegraean Fields view from Naples | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 458 m (1,503 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 40.827°N 14.139°E[1] |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Campi Flegrei (Italian) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Italy |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 40,000 years |

| Mountain type | Caldera[1] |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Campanian volcanic arc |

| Last eruption | September to October 1538[1] |

The area also features bradyseismic phenomena, which are most evident at the Macellum of Pozzuoli (misidentified as a temple of Serapis): bands of boreholes left by marine molluscs on marble columns show that the level of the site in relation to sea level has varied.

Geological phases

Three geological phases or periods are recognised and distinguished.[7]

- The First Phlegraean Period. It is thought that the eruption of the Archiflegreo volcano occurred about 39,280 ± 110 years (older estimate ~37,000 years) ago, erupting about 200 km3 (48 cu mi) of magma (500 km3 (120 cu mi) bulk volume)[8] to produce the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption.[9] Its Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) was 7. "The dating of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption (CI) to ~37,000 calendar years B.P. draws attention to the coincidence of this volcanic catastrophe and the suite of coeval, Late Pleistocene biocultural changes that occurred within and outside the Mediterranean region. These included the Middle to Upper Paleolithic cultural transition and the replacement of Neanderthal populations by anatomically modern Homo sapiens, a subject of sustained debate.[10] No less than 150 km3 of magma were extruded in this eruption (the CI eruption), traces of which can be detected in Greenland ice cores. As widespread discontinuities in archaeological sequences are observed at or after this eruption, a significant interference with ongoing human processes in Mediterranean Europe is hypothesized."[11] It is possible that these eruptions drove Neanderthals to extinction and cleared the way for modern humans to thrive in Europe and Asia.[12] The area is characterised by banks of piperno and pipernoid grey tuff at Camaldoli hill, as in the northern and western ridge of Mount Cumae; other referable deep products are those found at Monte di Procida, recognizable in the cliffs of its coast.

- The Second Phlegraean Period, between 35,000–10,500 years ago.[7] This is characterized by the Neapolitan yellow tuff that is the remains of an immense underwater volcano, with a diameter of c. 15 kilometres (9.3 mi); Pozzuoli is at its center. Approximately 12,000 years ago the last major eruption occurred, forming a smaller caldera inside the main caldera, with its centre where the town of Pozzuoli lies today.

- The Third Phlegraean Period, between 8,000 – 500 years ago.[7] This is characterized by white pozzolana, the material that forms the majority of volcanos in the Fields. Broadly speaking, it can be said there was initial activity to the southwest in the zone of Bacoli and Baiae (10,000–8,000 years ago); intermediate activity in an area centred between Pozzuoli, Spaccata Mountain and Agnano (8,000–3,900 years ago); and more recent activity towards the west, which formed Lake Avernus and Monte Nuovo (New Mountain) (3,800–500 years ago).

- Volcanic deposits indicative of eruption have been dated by argon at 315,000, 205,000, 157,000 and 18,000 years ago.[citation needed]

More recent history

The caldera, which now is essentially at ground level, is accessible on foot. It contains many fumaroles, from which steam can be seen issuing, and over 150 pools (at the last count) of boiling mud. Several subsidiary cones and tuff craters lie within the caldera. One of these craters is filled by Lake Avernus.

In 1538, an eight-day eruption in the area deposited enough material to create a new hill, Monte Nuovo. It has risen about 2 m (7 ft) from ground level since 1970.

The volcanic island of Ischia suffered three destructive earthquakes in 1828, 1881 and 1883, the most destructive occurring in 1883. It had a magnitude of 4.2–5.2, but caused catastrophic shaking assigned XI (Extreme) on the MCS scale. Extreme damage was reported on the island and over 2,000 residents perished.[13]

At present, the Phlegraean Fields area comprises the Naples districts of Agnano and Fuorigrotta, the area of Pozzuoli, Bacoli, Monte di Procida, Quarto, the Phlegrean Islands (Ischia, Procida and Vivara). [citation needed]

A 2009 journal article stated that inflation of the caldera centre near Pozzuoli might presage an eruptive event within decades.[14] In 2012 the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program planned to drill 3.5 kilometres (11,000 feet) below the earth's surface near Pompeii, in order to monitor the massive molten rock chamber below and provide early warning of any eruption. Local scientists are worried that such drilling could itself initiate an eruption or earthquake. In 2010 the Naples city council halted the drilling project. Programme scientists said the drilling was no different from industrial drilling in the area. The newly elected mayor allowed the project to go forward. A Reuters article emphasized that the area could produce a "super volcano" that might kill millions.[15]

A study from the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia shows that the volcanic unrest of the Campi Flegrei caldera from January 2012 to June 2013 was characterised by rapid ground uplift of about 11 cm (4 in), with a peak rate of about 3 cm (1 in) per month during December 2012. It adds that from 1985 to 2011 the dynamics of ground uplift were mostly linked to the caldera's hydrothermal system, and that this relation broke down in 2012. The driving mechanism of the ground uplift changed to periodical emplacement of magma within a flat sill-shaped magmatic reservoir about 3,000 m (9,843 ft) in depth, 500 m (1,640 ft) south from the port of Pozzuoli.[16]

In December 2016, activity became so high that an eruption was feared.[17] In May 2017 a new study by University College London and the Vesuvius Observatory published in Nature Communications revealed that an eruption might be closer than previously thought. The study found that the geographical unrest since the 1950s has a cumulative effect, causing a build-up of energy in the crust and making the volcano more susceptible to eruption.[18][19][20][21]

On 21 August 2017 there was a magnitude 4 earthquake on the western edge of the Campi Flegrei area.[22] Two people were killed and many more people injured in Casamicciola on the northern coast of the island of Ischia, which is south of the epicentre.[23]

A February 2020 status report indicated that inflation around Pozzuoli continues at steady rates with a maximum average of 0.7 cm per month since July 2017. Gas emissions and fumarole temperatures did not change significantly.[24][25]

On Sunday April 26, 2020, a moderate earthquake swarm hit Campi Flegrei caldera, which included about 34 earthquakes ranging between magnitude 0 and magnitude 3.1 with the swarm centered around the port city of Pozzuoli. The strongest quake in the Earthquake sequence was a magnitude 3.1, which is the strongest earthquake in the caldera going back to the last major period of unrest and rapid uplift in 1982-1984. However, no new fumaroles were reported.[26]

In its weekly bulletin of April 6 2021, the Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) reported that the Rione Terra (RITE) GPS tiltmeter had an average uplift rate of 13mm per month +/- 2mm. The strongest quake since March 29 2021 had been of magnitude 2.2, and the RITE GPS station had measured 72.5cm of uplift since January 2011.

Future hazards

While Campi Flegrei has seen more unrest lately,[27] an eruption in the area is unlikely to happen in the near future. Though a large-scale eruption like the one that occurred 39,000 years ago is very unlikely, a new caldera-forming eruption in the area is a possibility. Considering the unrest seen at the port of Pozzuoli, it is probable that the next eruption will take place within that region of the caldera.[citation needed]

Geoheritage designation

In respect of its 18th and 19th century role in the development of geoscience, not least volcanology, this locality was included by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) in its assemblage of 100 'geological heritage sites' around the world in a listing published in October 2022.[28]

Wine

Italian wine, both red and white, under the Campi Flegrei DOC appellation comes from this area. Grapes destined for DOC production must be harvested up to a maximum yield of 12 tonnes/hectare for red grape varieties, and 13 tonnes/ha for white grape varieties. The finished wines need to be fermented to a minimum alcohol level of 11.5% for reds and 10.5% for whites. While most Campi Flegrei wines are blends, varietal wines can be made from individual varieties, provided the variety used comprises at least 90% of the blend and the wine is fermented to at least 12% alcohol for reds and 11% for whites.[29]

Red Campi Flegrei is a blend of 50–70% Piedirosso, 10–30% Aglianico and/or Sciascinoso and up to 10% of other local (both red and white) grape varieties. The whites are composed of 50–70% Falanghina, 10–30% Biancolella and/or Coda di Volpe, with up to 30% of other local white grape varieties.[29]

Cultural importance

Campi Flegrei has had strategic and cultural importance.

- The area was known to the ancient Greeks, who had a colony nearby at Cumae, the seat of the Cumaean Sibyl.

- The beach of Miliscola, in Bacoli, was the Roman military academy headquarters.

- Lake Avernus was believed to be the entrance to the underworld, and is portrayed as such in the Aeneid of Virgil. During the civil war between Octavian and Antony, Agrippa tried to turn the lake into a military port, the Portus Julius.

- Baiae, now lying underwater, was a fashionable coastal resort and was the site of summer villas of Julius Caesar, Nero, and Hadrian (who died there).

- In Pozzuoli is the Flavian Amphitheatre, the third-largest Italian amphitheatre after the Colosseum and the Capuan Amphitheatre.

- The Via Appia passed through the comune of Quarto, entirely built on an extinguished crater.

- The Cave of Dogs, a famous tourist attraction during the early modern period, is on the eastern side of the Fields.

- Europe's youngest mountain,[30] Monte Nuovo, is here. A WWF oasis lies beside the enormous Astroni crater.

- The tombs of Agrippina the Elder and Scipio Africanus are here.

- At Baiae, now in the comune of Bacoli, the most ancient hot spring complex was built for the richest Romans. It included the largest ancient dome in the world before the construction of the Roman Pantheon.

- Astronomical broadcaster and writer Patrick Moore used to cite these Fields as an example of why the impact craters on the Moon must be of volcanic origin, which was thought to be the case until the 1960s.

- There is a theory that the Campanian Ignimbrite super-eruption around about 39,280 ± 110 years ago contributed to the demise of Neanderthal Man, based on evidence from Mezmaiskaya cave in the Caucasus Mountains of southern Russia.[31]

See also

- List of volcanoes in Italy

- Phlegra (mythology)

- Phlegraean Islands: in the same geologic area

- Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption

References

- "Campi Flegrei". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- "flegreo". Garzantilinguistica. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Giudicepietro, Flora. "Campi Flegrei - stato attuale".

- Howard, Brian Clark (22 December 2016). "One of Earth's Most Dangerous Supervolcanoes Is Rumbling". Nationalgeographc.com. National Geographic.

- "Getting to know the Phlgrean Fields". 11 May 2019.

- "The supervolcano in italy; Campi Flegrei". GeologyHub.

- Brand, Helen. "Volcanism and the Mantle: Campi Flegrei" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-10. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Fisher, Richard V.; Giovanni Orsi; Michael Ort; Grant Heiken (June 1993). "Mobility of a large-volume pyroclastic flow — emplacement of the Campanian ignimbrite, Italy". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 56 (3): 205–220. Bibcode:1993JVGR...56..205F. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(93)90017-L. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- Fedele, Francesco G.; et al. (2002). "Ecosystem Impact of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption in Late Pleistocene Europe". Quaternary Research. 57 (3): 420–424. Bibcode:2002QuRes..57..420F. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2331. S2CID 129476314.

- Neanderthal Apocalypse Documentary film, ZDF Enterprises, 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- De Vivo, B.; G. Rolandi; P. B. Gans; A. Calvert; W. A. Bohrson; F. J. Spera; H. E. Belkin (November 2001). "New constraints on the pyroclastic eruptive history of the Campanian volcanic Plain (Italy)". Mineralogy and Petrology. 73 (1–3): 47–65. Bibcode:2001MinPe..73...47D. doi:10.1007/s007100170010. S2CID 129762185.

- "Volcanoes Wiped out Neanderthals, New Study Suggests". ScienceDaily. Oct 7, 2010. Retrieved Oct 10, 2010.

The research is reported in the October issue of Current Anthropology

- S. Carlino; E. Cubellis; A. Marturano (2010). "The catastrophic 1883 earthquake at the island of Ischia (southern Italy): macroseismic data and the role of geological conditions". Natural Hazards. 52 (231): 231–247. doi:10.1007/s11069-009-9367-2. hdl:10.1007/s11069-009-9387-y. S2CID 140602189.

- Isaia, Roberto; Paola Marianelli; Alessandro Sbrana (2009). "Caldera unrest prior to intense volcanism in Campi Flegrei (Italy) at 4.0 ka B.P.: Implications for caldera dynamics and future eruptive scenarios". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (L21303): L21303. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..3621303I. doi:10.1029/2009GL040513.

- Antonio Denti, "Super volcano", global danger, lurks near Pompeii, Reuters, August 3, 2012.

- D’Auria, Luca; Susi Pepe; Raffaele Castaldo; Flora Giudicepietro; Giovanni Macedonio; Patrizia Ricciolino; Pietro Tizzani; Francesco Casu; Riccardo Lanari; Mariarosaria Manzo; Marcello Martini; Eugenio Sansosti; Ivana Zinno (2015). "Magma injection beneath the urban area of Naples: a new mechanism for the 2012–2013 volcanic unrest at Campi Flegrei caldera". Scientific Reports. 5: 13100. Bibcode:2015NatSR...513100D. doi:10.1038/srep13100. PMC 4538569. PMID 26279090.

- "Naples astride a rumbling mega-volcano".

- "Campi Flegrei volcano eruption possibly closer than thought".

- "One of World's Most Dangerous Supervolcanoes is Rumbling". 22 December 2016.

- "One of the world's most terrifying supervolcanoes is showing signs of reawakening in Italy". Independent.co.uk. 21 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2022-05-26.

- "Italian Supervolcano Could be Closer to Erupting Than Previously Thought".

- "M 4.3 - 5km NW of Monte di Procida, Italy". USGS.

- "Ischia earthquake: cheers go up as rescuers free third trapped brother". Guardian. 22 August 2017.

- "Campi Flegrei volcano (Italy) status report: no significant variations in activity". www.volcanodiscovery.com. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Campi Flegrei volcano (Italy) status report: continuing slow inflation". www.volcanodiscovery.com. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Campi-Flegrei-volcano-(Italy):Seismic swarm reported". www.volcanodiscovery.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Europe's super volcano". Deutsche Welle. 21 January 2022.

- "The First 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites" (PDF). IUGS International Commission on Geoheritage. IUGS. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- P. Saunders Wine Label Language pg 132 Firefly Books 2004 ISBN 1-55297-720-X

- "Pozzuoli: history, archeology, art, architecture, environment".

- Liubov Vitaliena Golovanova; Vladimir Borisovich Doronichev; Naomi Elancia Cleghorn; Marianna Alekseevna Koulkova; Tatiana Valentinovna Sapelko; M. Steven Shackley (October 2010). "Volcanoes Wiped out Neanderthals, New Study Suggests" (news release). Current Anthropology. 51 (5): 655–691. doi:10.1086/656185. S2CID 144299365.

Significance of Ecological Factors in the Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition

Further reading

- Volcanism in the Campania Plain: Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ignimbrites. Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-048166-1.

External links

- Phlegraean Fields tour (i Campi Flegrei)

- Phlegraean Fields

- Volcanological Excursion to Campi Flegrei

- Historical and Geological Introduction to the Neapolitan area

- Campi Flegrei Volcano’s Ancient Cycle Seems to End in Large Eruption

На других языках

[de] Phlegräische Felder

Die Phlegräischen Felder (altgriechisch Φλεγραία πεδία von φλέγειν phlégein ‚brennen‘; lateinisch Phlegraei campi; italienisch Campi Flegrei) sind ein etwa 20 km westlich des Vesuvs gelegenes Gebiet mit hoher vulkanischer Aktivität in der italienischen Region Kampanien. Die Phlegräischen Felder werden als Supervulkan eingestuft.- [en] Phlegraean Fields

[es] Campos Flégreos

Los Campos Flégreos son una vasta caldera volcánica situada a 9 km al noroeste de la ciudad de Nápoles,[1] cuya mayor parte está bajo el agua. Su nombre deriva del griego antiguo Φλέγραιος phlegraios, que significa «ardientes» y esta palabra es un cognado del latín flagrans, «ardiente».[ru] Флегрейские поля

Флегрейские поля (итал. Campi Flegrei, от греч. φλέγω — гореть[1]) — крупный вулканический район, расположенный к западу от Неаполя (Италия) на берегу залива Поццуоли (итал. Golfo di Pozzuoli), ограниченного с запада мысом Мизено (итал. Capo Miseno), а с востока — мысом Посиллипо (итал. Capo Posillipo), в свою очередь являющимся северной бухтой Неаполитанского залива. Сюда же относится и прибрежная полоса Тирренского моря (итал. Mare Tirreno) у Кум (итал. Cuma), а также острова Низида, Прочида, Вивара и Искья. Поля занимают площадь ориентировочно 10 × 10 км[2]. В 2003 году объявлена национальным парком.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии